The American Revolution was momentous at many levels, a break with traditional forms of monarchy and social deference undertaken, at its most radical, in the spirit of Thomas Paine’s famous call “to begin the world over again.” Yet the new American republic was also a slaveholding republic, destined to become the largest and wealthiest slaveholding nation on earth—a stark contradiction that now dominates interpretations of the American founding.

The most widely quoted denunciation of the Revolution’s foul dishonesty regarding slavery, cited by historians and pundits across the intellectual and ideological spectrum, came from the preeminent British man of letters, Samuel Johnson. Over the winter of 1775, at the behest of Lord North’s ministry, Johnson composed a pamphlet condemning the emerging American revolutionary cause. He focused on the Americans’ chief argument, first made famous by the antislavery patriot lawyer James Otis Jr., that without direct representation the colonists had no obligation to pay taxes levied by Parliament: no taxation without representation. Such treason, the Tory hardliner Johnson charged, made the Americans not misguided upstarts but “zealots of anarchy” who had to be silenced once and for all.

Entitled Taxation no Tyranny, Johnson’s pamphlet was widely regarded a failure, even by loyal British readers. Johnson’s chronicler James Boswell called it unworthy of its author. Johnson’s friend, the playwright Richard Brinsley Sheridan, dismayed by his “trifling and insincere” effort, considered writing a response but finally didn’t bother. It might have been forgotten had Johnson not included a passing dig at Englishmen who feared that suppressing the American protests would threaten their own liberties: “If slavery be thus fatally contagious,” Johnson wrote, “how is it that we hear the loudest yelps for liberty among the drivers of negroes?”

Johnson was an authentic and consistent as well as caustic critic of slavery and the slave trade, and he touched on a glaring incongruity: many of the leading proponents of American freedom enslaved black people. Yet given that he was defending the sovereign power of the world’s greatest slave-trading nation, which presided over a global empire of slavery that included the rebellious colonies, Johnson’s joke was also utterly disingenuous. And although he had a point about the “drivers of negroes,” Johnson also muffled how an unswerving abolitionist—James Otis Jr.—formulated and proclaimed the very ideas that he detested.

Johnson’s jibe had the effect of conflating slavery and the Revolution and besmirching liberals and abolitionists around the Atlantic world—not least the great British abolitionist Granville Sharp—who lamented the inconsistencies of American freedom and slavery yet supported the Revolution as a beacon of justice. Here lies another paradox: that the Revolution, although supported and to a large extent led by slaveholders, was also the most profound antislavery political event in history to its time. Between 1765 and 1783, the movement for American independence assembled, expanded, and politicized growing antislavery sentiments in the Atlantic world. In large portions of the rebellious colonies, Americans, black and white, concluded that the Revolution would be severely and perhaps fatally compromised unless it did away with the enslavement of Africans and their descendants.

This antislavery revolution within the Revolution came nowhere near destroying American slavery outright. But it challenged ancient assumptions about human bondage, created the first antislavery political campaigns and movements in modern history, and commenced the abolition of slavery throughout the Atlantic world. A pioneering black historian of the Revolution, Benjamin Quarles, once observed that confronting the history of slavery demands paying “careful attention to a concomitant development and influence—the crusade against it.” Following Quarles’s insight, let us examine the antislavery revolution inside the American Revolution.

In 1765, when protests over the Stamp Act initiated what would become the revolutionary cause, slavery was well established in all thirteen of the troubled North American colonies. Pennsylvania Quakers, after nearly eighty years of exceptional but fitful agitation, would not completely renounce it until 1776. Nothing existed in the way of a coordinated political attack on either slavery or the slave trade. Attempted armed insurrections by the enslaved, as in New York in 1712 and South Carolina in 1739, had been brutally suppressed.

By the end of 1784, a year after the Treaty of Paris completed American independence, antislavery campaigners, black and white, had all but won abolition in northern New England, enacted gradual abolition in Pennsylvania, Rhode Island and Connecticut, and inaugurated public protests and debates over its abolition as far south as Virginia—the first such abolitionist politicking and legislation in modern history. In five of the thirteen states, abolitionists had obliterated the hereditary property right essential to chattel slavery while declaring “repugnant,” in the words of Rhode Island’s abolition law, “the holding [of] Mankind in a State of slavery, as private property.” Only in the lower South was there no antislavery activity by whites, although even there the chaos caused by Revolutionary war, which led to slave resistance against both patriot and Loyalist enslavers, had badly damaged the plantation economy.

In 1784, meanwhile, a Confederation congressional committee consisting of Thomas Jefferson and two antislavery colleagues, the abolitionist David Howell and Howell’s good friend, the slaveholder-turned-antislavery advocate Jeremiah Townley Chase, proposed banning slavery from all of the western territories after 1800. Although the proposal failed in Congress by a single vote, it proved a preface to the Northwest Ordinance three years later that prohibited slavery north of the Ohio River. In 1787 the Federal Constitutional Convention authorized permanent abolition of American participation in the overseas slave trade, the first serious blow ever against that detested commerce in the name of a national government. In all, the Revolution had brought the commencement of abolition inside the states and the creation of a national government empowered to restrict its growth in areas under its direct purview and thereby, the abolitionists expected, hasten its destruction.

To be sure, the Revolution was not foundationally antislavery in the sense that the patriots stood united to abolish slavery; nor did it place American slavery, in Abraham Lincoln’s later phrase, in “the course of ultimate extinction,” as some celebrants of the Revolution have contended. Some of the most outspoken and effective antislavery advocates owned at least one slave for at least part of the time they fought for the cause. Describing the Revolution as flatly antislavery makes no more sense than describing it as flatly proslavery. Almost unquestioned anywhere in the world prior to the mid-eighteenth century—except, of course, by the enslaved—the institution of slavery still prevailed in the upper South and even parts of the lower North as well as in the Carolinas and Georgia.

In the lower South, slavery remained not just virtually unchallenged but fiercely defended by whites. Although many southern slaveholders were Loyalists, militantly proslavery patriots squared Revolutionary principles with human bondage, first, by proclaiming property rights in man were wholly legitimate and, second, by excluding Africans from the propositions of universal equality inscribed in the Declaration of Independence. If the Constitution empowered Congress to restrict slavery’s expansion, it also empowered Congress to approve slavery’s expansion. The hopes of some abolitionists in the aftermath of the Revolution that slavery would soon be but a speck on the American landscape—easily dismissed in retrospect as naïve and even bizarre, but sensible to sensible people at the time—were swiftly receding before the century was over.

Yet the fact that the Revolution did not abolish American slavery or immediately ban American participation in the slave trade should not be twisted to mean that the Revolution lacked a powerful antislavery dimension, let alone that it strengthened slavery. That slavery was on the defensive anywhere, as I have argued in these pages, was far more significant than the fact it still existed, given slavery’s virtually unassailable status less than a generation earlier. That slavery had even been contested by the end of 1785 in ten of the thirteen states, largely in response to popular antislavery pressure, is remarkable. That five of those states had either abolished slavery or commenced gradual abolition is extraordinary. (This does not include separatist Vermont, which adopted the first constitution in history to outlaw adult slavery in 1777 before gaining admission to the Union as the fourteenth state in 1791.) That Americans, even with slavery as deeply entrenched as it ever was in the lower South, also went on to establish a central government specifically authorized to limit its growth is, given slavery’s larger history, astounding.

American abolitionism made the greatest progress during the Revolution where slavery was weakest, which should come as no surprise. It does not follow, however, that northern slavery simply disappeared on its own. Throughout the North, proslavery advocates still wielded, at the outset, disproportional political power, and mounted strong resistance. In Massachusetts, for example, efforts to enact legislation banning slavery, debated as early as 1767, uniformly failed until abolitionists broke through in the courts. In Pennsylvania, the new unicameral patriot assembly twice rejected gradual abolition proposals until enacting the first of its kind in history in 1780. It took a decade of concerted agitation, chiefly through petitioning, before Rhode Island and Connecticut passed their gradual abolition acts in 1784; it would take fifteen years longer in New York and five years longer than that in New Jersey.

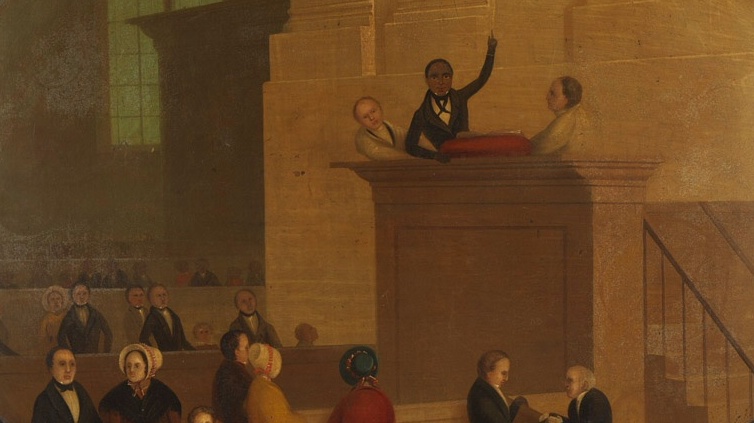

The adage that power never gives way without a struggle was no less true in the case of early American abolitionism. Antislavery’s success required the rise of what historians such as Sarah Gronningsater, Paul Polgar, and Manisha Sinha, overturning the received wisdom, have retrieved as the first abolitionist movement. That movement was underway years before the establishment of the first antislavery society in Philadelphia in 1775; it flowed naturally into the founding of more enduring antislavery organizations, among blacks and whites, after 1783. Long slighted as moderate if not conservative, irresolute, and ineffective, the early abolitionists have at last begun to receive their due as toughminded, determined reformers who, as the famous black abolitionist Reverend Peter Williams Jr. declared in 1808, withstood powerful men and “the strong gales of popular prejudice,” then “assailed the dark dungeon of slavery; shattered its rugged wall,” and bestowed on thousands of former captives “the blessings of civil society.” Although not the entire story, organized abolitionism and abolitionist protest, dating back to the 1760s, lay at the heart of the antislavery revolution within the Revolution.

Prior to 1787, the movement was, perforce, fragmented, its efforts divided among the separate provinces and later states; indeed, a good deal of the agitation was local. Still, the early abolitionists adapted and in some respects pioneered political strategies and tactics that would become essential to the antislavery cause until American slavery was finally abolished in 1865. Most conspicuously, they employed three political instruments: legislative instructions, petitions, and lobbying.

In May 1766, the Boston town meeting, chaired by Samuel Adams, instructed its representatives to the General Court to press for a law to close the slave trade as a step toward “the total abolishing of slavery from among us.” Thus began, in the wake of the repeal of the Stamp Act, a prolonged popular campaign in Massachusetts that would soon enough engage abolitionists white and black, enslaved and free.

A year later, the Worcester town meeting called upon its representative to use his “Influence to obtain a Law to put an End to that unchristian and impolitick Practice of making Slaves of the human Species in this Province; and that you give your Vote for none to serve in His Majesty’s Council, who you have Reason to think will use their influence against such a Law.” A freshet of pamphlets and sermons backed these efforts. Although an abolition bill failed in 1767, the movement persisted, issuing further instructions and publishing new pamphlets, including the young patriot James Swan’s rousing Dissuasion to Great-Britain and the Colonies.

In 1773 an enslaved Bostonian named Felix Holbrook sent a politely worded freedom petition, on behalf of the local and neighboring black population, to the legislature and the Royal governor, Thomas Hutchinson, which touched off successive rounds of petition campaigns. The following year, an enslaved man in Connecticut named Bristol Lambee directed a freedom petition to “the SONS of LIBERTY in CONNECTICUT” on behalf of “a number of poor Africans.” Five years later, during the war with Britain, petitions arrived at the state legislature. One of them, signed by two enslaved men named Prime and Prince, was cowritten by the secretary of the Fairfield Sons of Liberty, Jonathan Sturges, who, though himself recorded as the owner of three slaves, would go on to become an antislavery stalwart in the early US Congress.

The former slave Prince Hall, leader of the free black community in Boston (and not the same as the Connecticut Prince), also picked up the petitioning after the war began. Alongside protests by antislavery whites and in coordination with abolitionist legislators such as Nathaniel Peaslee Sargent, Hall’s petition led to an “Act for preventing the Practice of holding persons in Slavery,” which would have freed all enslaved persons over age twenty-one “whether black or other complexion.” The most emphatic abolition bill of its time, it passed through two readings in the lower house before being sidelined. In Virginia a freedom petition sent to the House of Delegates by an enslaved man named George in 1778 initiated the political campaign, picked up by Quaker abolitionists, that led to the enactment of the important manumission law in 1782, despised by proslavery hardliners, that struck down old and formidable obstacles to freedom in the largest slaveholding state. In Pennsylvania, a group of free black advocates memorialized the legislature in 1781 to protest proslavery efforts to overthrow the state’s gradual abolition law.

These instruction and petition campaigns, which were replicated across New England as well as in the lower North, were remarkably sophisticated, aiming their message at specific legislators as well as the public at large to gather support. They also united slavery’s opponents across the color line. Holbrook and his fellow enslaved petitioners, while making a point of speaking in the name of a distinct black community, also made common cause with white abolitionists, sharing an idea of universal equality that transcended and challenged ideas of race, publicizing the petitions, gaining the support of town meetings in and around Boston, and coordinating legislative strategy and tactics. Bespeaking the abiding realities of racial divisions, later white and black abolitionists created separate antislavery institutions, but they worked closely together on efforts that ranged from petitioning Congress to providing legal services to slaves and educating free and enslaved black children.

Abolitionist lobbying came into its own in the greater Philadelphia area, most conspicuously thanks to the former slaveholder and Delaware Quaker abolitionist Warner Mifflin. In 1782 Mifflin, an imposing figure who stood roughly seven feet tall, travelled with two other antislavery slavery agitators to Richmond, Virginia, where they buttonholed legislators in a successful effort to pass the state’s important manumission law. Thereafter he lobbied, among other bodies, the Delaware legislature, the Confederation Congress, and, in 1790, the first US Congress.

The dispersed agitators knew of each other’s work. Making certain that they did was the most remarkable of the early American abolitionists, the émigré Quaker Anthony Benezet. A veteran antislavery crusader by the mid-1770s, Benezet, from his base in Philadelphia, had created the transatlantic network of antislavery communications that, among other things, helped inspire the British abolitionist Sharp in the landmark Somerset v. Stewart case in 1772, whose outcome was widely perceived as having outlawed slavery inside Britain (although not, of course, in Britain’s colonies, home to the vast majority of British-owned slaves). Benezet was a one-man clearing house, supplying agitators with propaganda as well as intelligence and moral support.

Where legislative action failed, enslaved men and women looked to the courts. Freedom suits had been pursued well before the Revolution, in which slaves sought to free themselves by claiming the papers securing their bondage were defective. As the Revolution approached, these efforts became entwined with rising egalitarian sentiments, as some slaves sued on the grounds that slavery was simply illegal, and, particularly in Massachusetts, all-white juries agreed.

In 1781 an enslaved woman in the Berkshires called Mum Bett sued in a case that she, her lawyer Theodore Sedgwick, and his co-counsel Tapping Reeve turned into a test of whether the 1780 Massachusetts constitution had effectively abolished slavery. They succeeded (and she took the name Elizabeth Freeman), and soon after another Massachusetts slave, Quock Walker, pressed his own case. The ruling, delivered by the chief justice of the state’s supreme court, was taken as a virtual abolition of slavery. Like Freeman, Walker collaborated with his white antislavery attorneys, Levi Lincoln and co-counsel Caleb Strong, in devising their abolitionist arguments. Elsewhere, where abolitionists and their supporters would in time manage to win gradual abolition laws, slaveholders remained wary of the courts.

Violent dislocation during the war also opened numerous opportunities for the enslaved to strike out on their own. This included many thousands, especially in the South and lower North, who ran to British lines and even joined the redcoat military, searching for freedom as best they could find it. But “to the most unobservant field hand,” as Benjamin Quarles observed, “it must have been plain that England had not the remotest idea of making the war a general crusade against slavery, especially since so many of her loyalist supporters would have protested bitterly.” Other slaves saw greater opportunity in siding with the patriots. And while the war hampered antislavery activity, abolitionists carried on with their work even in some fearsomely chaotic places like New Jersey, whose abolitionist governor William Livingston continued trying, as he put it, “to lay the foundation” for emancipation.

The American antislavery upsurge had intellectual as well as a political dimensions, as revolutionary natural rights ideology merged with religious antislavery protests. Prior to the 1760s Quaker religious injunctions, focused on the Golden Rule and the inward light, dominated antislavery thinking. Thereafter, though, secular themes stemming from the Atlantic Enlightenment became central. The Massachusetts lawyer and orator James Otis Jr., who was a friend of Thomas Paine and mentor to Samuel Adams—the figure whose ideas on taxation and representation Samuel Johnson polemically linked to slavery and slaveholders—famously connected Lockean natural rights to antislavery in a courtroom address in 1761. (“Not a Quaker in Philadelphia,” a shocked John Adams later reported, had “ever asserted the rights of negroes in stronger terms.”) Over the ensuing twenty years, abolitionists, with important added support from Methodists and other evangelical Protestants, turned universal equality into their core principle.

Patriot abolitionists, white and black, recognized the contradiction within the Revolution that Johnson mocked. Writing in 1776, the devoted abolitionist New Jersey Presbyterian minister Jacob Green, in one of a multitude of examples, called it “a dreadful absurdity…that people who are so strenuously contending for liberty, should at the same time encourage and promote slavery.” The formidable Connecticut abolitionist cleric Lemuel Haynes noted the Declaration of Independence’s professions about liberty but also underscored that “Liberty is Equally as pre[c]ious to a Black man, as it is to a white one.” Yet instead of seeing the contradictions as proof of American deceit, abolitionists, including those most bitterly disappointed by the failure to abolish slavery anywhere prior to 1776, embraced the Revolution. Haynes, for example, best known as the first black man ordained as a mainstream Protestant minister in America, served as a Minuteman and later a patriot army soldier and thereafter remained a steadfast defender of American republican ideals, “in principle,” according to his first biographer, “a disciple of Washington.”

By the time they began enjoying their first political successes in the 1780s, patriot abolitionists had hammered out a view of the Revolution that was not only antislavery but explicitly opposed to racial enslavement. The Pennsylvania Act for the Gradual Abolition of Slavery, for example, tied what it called the imminent American victory over the British to the slaves’ liberation from a “state of thralldom.” The act emphasized that “a difference in feature or complexion” had become a pretext for enslavement, desecrating “the work of an Almighty Hand.” Weaned from ancient prejudices, “with kindness and benevolence towards men of all conditions and nations,” the Pennsylvanians vowed to end “as much as possible the sorrows of those who have lived in undeserved bondage,” knowing that more would be necessary but at least adding “one more step to universal civilization.”

Even as a few, for a time, spoke of moving to Africa, black abolitionists as well as white understood the Revolution in these terms. A 1779 petition from a group of nineteen enslaved New Hampshire men, for example, including a leader of the community named Nero Brewster, began by asserting “that the God of Nature gave them Life and Freedom upon the terms of the most perfect Equality with other men.” Then, the petition charged, “through ignorance and brutish violence of their native countrymen,” they and their posterity had been compelled “to drag on their lives in miserable solitude.” Brewster and the others knew well the authors of their misery. But they also recognized that the creed of equality inspiring the Revolution could become the foundation for their own claims to freedom—a creed that, if honored, would lead responsible legislators to abolish slavery. “Put us upon the equality of freemen,” the petition asked, and the petitioners would show “to the world our love of freedom, by exerting ourselves in her cause in opposing the efforts of tyranny and oppression over the country in which we ourselves have been so long injuriously enslaved.”

Antislavery politics fared far less well in the upper South, but similar dynamics were at work. “Though our bodies differ in colour from yours; yet our souls are similar in a desire for freedom,” one “Vox Africanorum” would observe in a Maryland newspaper in 1783, while expressing support for the patriots’ victory. “Every principle which has led America to freedom and greatness,” he insisted, forbade the perpetuation of slavery.

The antislavery struggle began in earnest at the national level in 1784, when the congressional committee consisting of Jefferson, Chase, and Howell nearly succeeded in its effort to ban slavery in the western territories after 1800. The free-soil principle behind that effort was not presumed after the Revolution; it had to be asserted, the beginning of what would become a long crusade to contain slavery’s expansion beyond the states where it already existed. The Northwest Ordinance, apart from banning slavery in the Northwest Territory, salvaged that principle and inscribed it in national law, which the new Congress under the US Constitution would reenact in 1789.

The struggle continued at the Federal Convention that framed the US Constitution in 1787. It is commonly noted that nearly half of the Constitution’s framers were slaveholders, an important if unsurprising fact for a group of late eighteenth-century American gentlemen drawn from all parts of the county. No less important, though, were the framers who were antislavery, the latter a category that scarcely existed at the outset of the Revolution, as well as the slaveholding framers who nonetheless denounced the institution and believed it should and would fade away.

Of the thirty delegates from states north of Maryland, at least six were members, soon to become members, or sympathizers with abolitionist societies, including the president of the Pennsylvania Abolition Society, Benjamin Franklin; one of the first members of the New-York Manumission Society, Alexander Hamilton; and the co-founder, with the Quaker abolitionist Mifflin, of Delaware’s first abolitionist society, Richard Bassett. Numerous other delegates were known publicly as strong antislavery advocates, among them such impressive names as John Dickinson, Rufus King, Gunning Bedford Jr., and, from Massachusetts, Levi Lincoln’s co-counsel in the Quock Walker cases, Caleb Strong. Still others, like the remainder of the Pennsylvania delegation, were broadly antislavery. As the proslavery delegates scanned the faces of their northern colleagues they sensed, as Pierce Butler of South Carolina remarked at the convention, that “some gentlemen within or without doors, have a very good mind” to take from the Southern states “their negroes.”

No one doubted that the convention from the start forsook giving the new national government authority to interfere directly with slavery, either in the states where it already existed or in the states that had enacted abolition. This had nothing to do with appeasing slaveholders. Contrary to common misperceptions, the convention was not omnipotent; nor, in creating a new federal plan, was it able to establish an omnipotent national government. To be sure, the framers were eager to regularize commerce between states and with foreign countries, and to nationalize power over the currency. But they never contemplated creating a national government with the authority to interfere with property and status laws internal to the states, including laws that either established slavery or abolished it. Slavery where it existed would be tolerated as a state institution; likewise, the new national government would not impede states in abolishing slavery inside their borders.

Yet this did not foreclose attacking slavery indirectly at the national level. Abolitionists and their antislavery colleagues were determined to advance the cause by authorizing the new federal government to restrict slavery’s growth in areas under its own jurisdiction. While the Confederation Congress, meeting in New York, passed (to the surprise of some) the Northwest Ordinance, restricting slavery’s geographic expansion, antislavery delegates at the Federal Convention were fixed on restraining its numerical expansion by authorizing the new government to abolish participation in the Atlantic slave trade, an unprecedented move then widely understood as a necessary first step toward abolishing slavery itself.

Abolitionists had long petitioned over the slave trade at the level of provincial and state politics; in 1783, a delegation of Pennsylvania Quaker abolitionists had presented a slave trade petition to the Confederation Congress. Now the Pennsylvania Abolition Society prepared a memorial that implored the framers “to make the suppression of the African trade in the United States a part of their important deliberations,” and the group bid Benjamin Franklin to bring it to the floor of the Federal Convention.

The existing Confederation government had no authority over the trade, which was left in the hands of the individual states. Participation in the trade, strongly opposed for decades, came under mounting attack in 1787 at the state level, chiefly out of widespread revulsion but also out of fear that adding any more slaves from Africa would invite insurrections. (South Carolina had actually closed its trade in March 1787 for short-term economic reasons but only temporarily, with the eager presumption that it would reopen.) Yet while the time to act now seemed to the abolitionists propitious as well as morally urgent, the lower South states would fiercely resist surrendering their power to do absolutely as they pleased on anything connected with slavery, including the slave trade. To lower South planters, still recovering from the devastation of the war, preserving state control over the slave trade was particularly important, even imperative, given what they foresaw as the inevitable need for human cargo from Africa. But many planters also feared that granting the national government the power to abolish the slave trade would serve as what they came to call an “entering wedge” to enact a national emancipation.

For tactical reasons, Franklin decided against presenting the strongly worded PAS petition to the delegates early in the convention’s proceedings lest it “alarm some of the southern states,” but he assured the abolitionists that “the great object of the memorial would be taken under consideration.” So it was, weeks later, after a committee dominated by an unyielding proslavery South Carolina delegate presented a draft constitution that maintained the existing division of power and barred the national government from exercising any authority whatsoever over the slave trade. The abolitionist and antislavery delegates, led by Gouverneur Morris, representing Pennsylvania, exploded. In response the lower South defiantly vowed to bolt the convention if they did not get their way; but the antislavery side, with vital backing from Virginia, forced them to eat their words. A committee was tasked with reaching a bargain, which included three issues not yet voted on by the convention: authority to abolish the slave trade, authority to tax the trade, and a southern-imposed supermajority requirement for all navigation laws. (The convention had already approved a fourth item that was up for discussion, banning a tax on exports.) The opponents to the slave trade won all three.

Proslavery delegates led by Charles Cotesworth Pinckney were able to salvage a twelve-year moratorium on authorizing abolishing the trade, to soften what their apprehensive planter constituents would regard as a grievous blow. Pinckney then maneuvered, with the aid of New England delegates, to tack on another eight years. Still, the resulting slave trade clause, along with the Northwest Ordinance, was one of the first national victories to stem from the antislavery impulses of the Revolution. Even with the moratorium—which, as it happened, prompted no sudden flood of slave trade imports—mainstream abolitionists like Benjamin Rush hailed the clause as a historic blow for freedom, the first of its kind anywhere.1

To be sure, the framers did not create an antislavery Constitution, and they certainly offered some concessions to the slaveholders, including the three-fifths clause and a fugitive slave clause. Even these concessions, however, hardly provided slavery the ironclad guarantees that Southern supporters of the Constitution later boasted they did. The three-fifths clause, for example, could not prevent the North from in time widening its majority in the House of Representatives. The fugitive slave clause—a measure prompted by the success of northern abolition—mandated no federal role and avoided referring to slaves as property, thereby sustaining the exclusion of slavery from national law. As a provision for state comity, it stipulated no reward for capturing runaways or punishment for shielding them. To gain federal fugitive slave laws, proslavery southerners had to move beyond the Constitution.

Far more powerful than any constitutional concession in protecting slavery was what has come to be known as the “federal consensus,” barring federal interference with slavery in the states where it already existed. The First Congress, in response to abolitionist petitions in 1790 bidding representatives to use their powers to the utmost against slavery and the slave trade, explicitly affirmed that consensus. Yet the House also rebuffed efforts by the lower South to turn the consensus into an absolute prohibition of federal action on anything to do with slavery that was not explicitly granted by the Constitution. Apart from reapproving the Northwest Ordinance, the First Congress affirmed what Elbridge Gerry of Massachusetts called Congress’s right to “intermeddle” in the Atlantic slave trade short of abolition before 1808. In the debate over the abolitionist petitions, meanwhile, Gerry’s congressional colleague James Madison noted that “Congress have certainly the power to regulate the subject of slavery” in the western territories—the issue that, when pressed by antislavery northerners, in time helped spark the Civil War.

Neither wholly antislavery nor pro-slavery, the Constitution provided a model, as the neglected but unrefuted work of the historian Don Fehrenbacher established more than thirty years ago, for a federal government where either slavery or antislavery might prevail. The balance of power shifted dramatically in favor of slavery after the introduction of the saw cotton gin and the use of improved seed varieties, beginning in the mid-1790s, initiated an unforeseen revolution in cotton production—a cornerstone of what historians describe as the Atlantic world’s second slavery. With the opening of southwestern territories to slavery, an immense, and immensely lucrative, domestic slave trade arose, quickly superseding the close of the Atlantic slave trade. Through the 1840s, meanwhile, as Fehrenbacher showed, the slaveholders generally enjoyed the upper hand in national affairs due to their skillful use of political power, including the judiciary, insuring, for example, that the Congress would not interfere with the domestic slave trade. Only in the 1850s did Lincoln, Salmon P. Chase, Charles Sumner, and others break through with the case for the Constitution’s antislavery possibilities, seeking slavery’s extinction by exercising federal power to halt its expansion.

None of this would have been possible, however, without the antislavery revolution inside the American Revolution. In June 1788, three months after he submitted the last of his contributions to what would become known as the Federalist Papers, the abolitionist John Jay, who would become the first chief justice of the Supreme Court, wrote to the president of a newly established British organization, the Society for Promoting the Manumission of Slaves. Jay welcomed the group to the fray, but cautioned that, even in America, antislavery opinion had only recently gained momentum. “Prior to the great revolution,” he observed, “the great majority or rather the great body of our people had been so long accustomed to the practice and convenience of having slaves, that very few among them even doubted the propriety and rectitude of it.”

Much work remained to be done, Jay added—“the whole mass is far from being leavened,” he wrote—but something had shifted dramatically. As Jay understood it, the “great revolution” was also an antislavery revolution. The struggle that followed would take far longer and be far bloodier than he either hoped or imagined it would. Still, while nothing was predestined, the antislavery revolution inside the American Revolution would prove to be the beginning of slavery’s destruction, not just in the newborn United States but throughout the Atlantic world.