One man disappears underground as another emerges on the surface. A third squats on the road between them, turning between the two sewer holes, which they climb into and out of without support. None of the men are wearing proper clothes. The one aboveground is in white undergarments that stand out against the surrounding filth. The other two are bare-chested, their limbs slick with grime, hair wet and flattened. Signs of their labor are strewn nearby: a bucket, a rusty chain, a few crude rods. At the edge of the frame the soles of shoes can be made out, walking away on cleaner ground.

This is one in a series of extraordinary photographs that Sudharak Olwe made between 1999 and 2000 of Mumbai’s Safai Karamcharis, or sanitation workers. Their job is to collect the city’s trash and sweep its streets, clean sewers and septic tanks, load and unload garbage trucks, and sort waste at dumping grounds. Many of them labor with primitive tools and without uniforms, as Olwe’s pictures show. In one, workers sift through mounds of waste with scraggly brooms and rakes. In another, two workers in vests and shorts sit atop trash in a garbage truck. In a third, a worker glares at the camera as he stuffs a dead dog into a bin.

Perhaps Olwe’s most damning image is a portrait. The face of a Safai Karamchari is seen from above; his body is invisible beneath a black pool of sewage. He has been sent in to unclog a sewer line, which is standard practice in India. The law mandates protective equipment for the task: oxygen masks, body suits, gloves, boots. But these are almost never provided, as countless investigations have made clear. Safai Karamcharis are thus brought into contact with human waste, which causes diseases like cholera, bronchitis, and tuberculosis, as well as with the noxious gases that build up underground. These include hydrogen sulfide, which can blind, and carbon monoxide, which can kill.

Those sent down to rescue asphyxiated workers face the same danger. In May a forty-five-year-old Safai Karamchari named Nandakumar entered a septic tank in Ramnagar, Uttar Pradesh, and lost consciousness, at which point his son, and after him two more relatives, rushed in to help. None survived. In 2022 India’s federal minister for social justice, Ramdas Athawale, told Parliament that, in the previous five years, 330 sanitation workers had died inside septic tanks and sewage lines, which is certainly an undercount. The social movement Safai Karmachari Andolan (SKA) believes that nearly two thousand die every year underground. Deaths in these gas chambers are reported daily in newspapers, where they are described as accidents.

That Safai Karamcharis are made to enter sewers is a legacy of the caste system. Considered an impure task by Hindus, the disposal of human feces has for centuries been done by the lowest Dalit, or untouchable, subcastes. This labor relation persists across South Asia: an estimated 98 percent of India’s Safai Karamcharis are Dalit, as are the majority of sanitation workers in Bangladesh, Nepal, and Pakistan. Across the subcontinent, they labor in hazardous conditions and face social ostracization. In June 2017 Irfan Masih, a Christian Safai Karamchari in Pakistan’s Sindh province, died after three doctors refused to treat his sludge-covered body. True believers stay clean during Ramadan.

For decades the Indian state has ignored the human costs of sanitation work in favor of endless talk about technological improvements. Most recently, the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) included a scheme in its 2023 federal budget to entirely mechanize the cleaning of septic tanks and sewer lines. The item reads, in its entirety, “All cities and towns will be enabled for 100 percent mechanical desludging of septic tanks and sewers to transition from manhole to machine-hole mode. Enhanced focus will be provided for scientific management of dry and wet waste.”

To imagine that India’s rickety sanitation infrastructure can be mechanized overnight is sheer fantasy. In 2019 New Delhi (population over 16 million) rolled out its first fleet of two hundred sewer-cleaning trucks. Two years later Mumbai (population over 21 million) purchased its first thirty-seven sewer-cleaning machines. Most urban centers have neither. Yet the federal budget allocates nothing for new sanitation technology, let alone alternative employment for thousands of Safai Karamcharis, who go entirely unmentioned.

Like access to clean water and electricity, water-borne sanitation is a modern utility desired by people across India, including upper-castes. This is one reason governments periodically make a spectacle of expanding and modernizing the system. Yet rather than respect sanitation as a profession, most Indians look down on it as a duty that Dalits were born to perform. Embracing the material benefits of modernity without letting go of the hierarchical ideology of caste, upper-caste Indians have grown murderously indifferent to the plight of Safai Karamcharis, who work in public places—roads, dumps, railway tracks—in abominable conditions that flagrantly violate the law. Two years ago the scholars Shiva Shankar and Kanthi Swaroop published a scathing article in which they charge Indian society with genocide against sanitation workers.1 “In a country that records the death of a sanitation worker by asphyxiation in a septic tank or sewer every two days,” they write, “its citizens have chosen to apathetically look away.”

The caste system is older than Hinduism as we know it today. Historians trace its rise to between 1500 and 500 BC, when a group known as the Aryans arrived in the subcontinent from Central Asia and enshrined a belief system known as Vedism, the precursor of Hinduism. Early Vedic texts sketch out the three main principles of caste. The first is professional identity: all members of a Varna, or caste, were required to perform the same job. Brahmins were priests; Kshatriyas were warriors; Vaishyas were peasants and artisans, later traders; Shudras were manual laborers. The second was endogamy: marriage outside caste was forbidden. The third was hierarchy: some castes were considered superior to others, with Brahmins at the top, above Kshatriyas, followed by Vaishyas, with Shudras at the bottom. “By the mid-first millennium,” Romila Thapar writes in The Penguin History of Early India, caste status “was reiterated in the theory that the first three varnas are dvija, twice-born—the second birth being initiation into the ritual status—whereas the shudra has only a single birth.”2 Subsequently a fifth group emerged, which performed a wide range of jobs, including waste disposal, ropework, midwifery, tanning, and washing clothes. They were considered avarna, or outcast. These were the so-called untouchables. Today they are known as Dalits—a term of self-definition adopted by the twentieth-century political leader and scholar B. R. Ambedkar, himself born into a Dalit community in Maharashtra.

Unlike Catholicism, which was overseen by the Vatican, there was never a single Vedic dogma or ecclesiastical authority. Unlike feudalism in Europe, which was enforced by the crown, no king ever signed a Vedic charter. Even the image of a fourfold system is misleading: Varnas were not homogenous groups but broad categories, with hundreds of endogamous clans, or jatis, within each. Caste dynamics varied widely from time to time and place to place, as new jatis formed and were assigned a place in the old order. The system was both rigid and formless; it ruled everywhere but from nowhere; few benefited and most adhered. How to make sense of these contradictions?

The historian Ram Sharan Sharma has argued that belief in the transmigration of souls was central to preserving the caste system: by following Vedic laws, you might be reborn into a higher caste. Just as crucial was a belief in fairly literal notions of purity and pollution. By a circular logic, castes that did “pure” work were higher in the hierarchy and those that did “polluted” work were lower. Priesthood was pure because it was done by Brahmins, and Brahmins were pure because they were priests; cremation was polluted because it was done by Dalits, and Dalits were polluted because they did cremation. Savarnas—Hindus from within the four Varnas—went to great lengths to avoid Dalits, afraid of being polluted by touch or sight or even shadow.

Yet it would be misleading to understand caste as just the outcome of atavistic hatred or superstition. It was also a regime of exploitation, with resources like land, money, and knowledge monopolized by savarnas, and Dalits obligated to work for the village for meager compensation. As both a belief system and a labor relation, Vedism’s ancien régime proved remarkably enduring in the face of internal reform movements like the Bhakti tradition that originated around the seventh century CE, which broke with Brahmanical dogma but failed to overturn the material conditions that kept caste locked in place.

As Christianity, Islam, and Sikhism took root in the subcontinent—in the first to third centuries, seventh century, and fifteenth century, respectively—millions of Dalits converted, only to find the old Vedic hierarchy recreated in their new religions, albeit in less vicious forms. Sikhism divided between landowning Jat Sikhs and landless Dalit or Mazhabi Sikhs. In Islam the split was between Pasmandas (which translates to “left behind”), among them artisans or small farmers, and Ashrafs, among them traders and landlords; a few Dalit Muslim jatis formed as well. Dalit and savarna converts to Christianity prayed in different churches. The contemporary Malayalam poet and intellectual M.B. Manoj, in a poem addressed to “Yesu,” or Jesus Christ, conveys the ambivalent plight of Dalit Christians:

We are not the ones who whipped you;

we even gave our land to hang your pictures

and adorn your statues

that lean forward from the Cross.Why, Yesu, instead of talking straight,

did you ever lead us along

this tortuous path?3

The caste system largely withstood the onslaught of modernity by taking on new forms. Brahmins traditionally held a monopoly over knowledge; today they dominate media, academia, and technology. Big businessmen are almost all Vaishyas, like the billionaire Gautam Adani. Kshatriyas are landlords in north and central India, though they have largely disappeared elsewhere. Shudras still control agriculture. Untouchables were traditionally forbidden to own land; Dalits remain largely without property. (They comprise over 32 percent of Punjab’s population but own only 4 percent of the land.) They work in large numbers as agricultural laborers, on construction sites and factories, and in professions like leatherwork, cremation, and sanitation. Across rural India they remain barred from accessing water tanks, wells, temples, and much else. The penalty for intercaste love remains severe across rural India, where couples are routinely lynched in “honor killings.” Provisions for affirmative action for Dalits—taking the form of “reservations” or quotas in government jobs and education institutes—are virulently opposed by most upper-caste savarnas, who disguise their casteism under appeals to “merit.”

Of all jobs reserved for Dalits, those perceived to be most polluted are those related to waste and death. The jatis at the very bottom sweep streets, cremate bodies, dispose of animal carcasses, and deal with shit. For the longest time, excreta was overwhelmingly gotten rid of in a process now termed “manual scavenging.” What this means is that Dalits used brooms, baskets, and their bare hands to take away human waste from dry latrines—shallow pits dug in the ground. Even today, Dalit women in a few villages still empty dry latrines as their jajmani, their hereditary duty, for which they are given token compensation. Sudharak Olwe has made a separate series documenting their lives. One suite of six photographs follows Meenadevi, a fifty-eight-year-old woman who cleans dry latrines in the state of Bihar’s Rohtas district. She bends down near an open toilet, gathers dried excreta into a broken bamboo basket with a stick and cardboard pads, and tosses the waste in nearby fields.

Early visitors to India noted the practice of manual scavenging. In 629 AD, the Chinese traveler Yuan Chwang wrote that “scavengers have their habitations marked by a distinguishing sign. They are forced to live outside the city, and they sneak along the left when going about in hamlets.” The subject was also taken up by anticaste writers like the Telugu poet Pālkuriki Somanātha, who in the thirteenth century wrote a remarkable parable titled “The Brahmin Widow and the Untouchable God.” Its hero, Śiva, is a tanner from the Madiga caste, which has historically done both leatherwork and scavenging. Sūrasāni, a Brahmin widow, invites Śiva into her house, which violates caste strictures, enraging the Brahmin neighbors. They fear the loss of their caste privilege, and with it their caste identity. “Our village has become an Outcaste colony,” they complain to the king. “She’s thrown our caste into an abyss of darkness.”4 An investigation is conducted, which reveals that Śiva is a reincarnation of God, who has taken the form of a Madiga to test the faithful. The Brahmins repent.

The scholar Joel Lee groups together the myriad jatis that today work in waste disposal as “sanitation labor castes.” (A derogatory umbrella term in Hindi is “Bhangi.”) A brief list would include Chuhras, Dhanuks, Doms, Halalkhors, Mangs, Mazhabis, and Mehtars in North India and Chakliyars, Dombans, Madigas, Pakis, Rellis, Thottis, and Yanadis in the south. Most are officially registered as Hindu. Some are Muslim, like the Halalkhors and Lalbegis. Many Madigas are Christian. Mazhabis are Sikh. More populous groups like Doms and Chuhras, as their oral histories attest, have been engaged in waste disposal for centuries. Smaller subcastes like the Dhanuks generally entered sanitation in the nineteenth century, as their “traditional” occupations (like basket weaving) were rendered obsolete by mass production.

The British inherited a patchwork sanitation system when they officially took control of the subcontinent in the mid-eighteenth century. Even in Delhi, the former Mughal capital, waste was handled at the level of theneighborhood, as Dalits went door to door to gather the excreta that upper-caste Hindu and Muslim families left aside for them, which they carted out of the city and sold as manure. As urban areas expanded with colonialism, brought into the ambit of imperial trade, the British nonetheless allowed this practice to continue, rather than laying down a modern sewage system. Change only came in the aftermath of the 1857 Sepoy uprising, when Indian cities were divided into British and native quarters, in part to protect colonial soldiers from diseases that spread from the unwashed masses. Drains, sewage lines, and modern garbage collection were introduced in the former areas but withheld from the latter. “As the problem of ‘cleaning up’ the subcontinent was considered to be too enormous to even be contemplated, the British sought to alleviate their fears by segregating themselves into residential enclaves away from the Indigenous population,” Susan Chaplin notes in her study The Politics of Sanitation in India.5

Sanitation labor castes won greater visibility under British rule, which was not always to their benefit. Beginning in the 1880s, the British formalized the practice of manual scavenging in native areas, but professionalization did not put an end to stigma, as the invisible hand of caste drew Dalits into a job that upper-caste Hindus scorned. In his important study Untouchable Freedom, Vijay Prashad shows how sanitation labor jatis were hired by the colonial state as cleaners, who were then overseen by upper-caste contractors.6 In effect, Dalits went on with their hereditary duty, for which they were now paid a meager salary. Many were even made to purchase their own uniforms.

In the 1910s and 1920s the colonial government introduced forms of electoral representation, which in turn required census-taking. As voter numbers became available, upper-caste Hindu leaders were given a rude shock, finding themselves sharing the terrain of democracy with larger populations of Muslims, Dalits, and Adivasis than they had imagined.7 An alliance between these groups would have put paid to upper-caste hegemony. To avert this disaster, Hindu supremacist organizations launched an ambitious campaign to convince Dalits and Adivasis to join the Hindu political bloc. Sanitation castes became the first targets of this new conviviality.

Joel Lee revisits this encounter in his recent book Deceptive Majority. Through great archival labor, he reveals that sanitation labor jatis of north India were long culturally separate from Hinduism, widely viewing “themselves as members of a qaum or ummat—a cohesive, autonomous socioreligious community—centered on Lal Beg, an antinomian prophet (paighambar) that narratively moved in an Islamacite world.”8 Hindu missionary groups like the Arya Samaj sent volunteers into ghettoes where Safai Karamcharis lived to destroy this heritage. They concocted a Hindu pedigree for sanitation labor castes, in the form of a genealogical connection to Rishi Valmiki, author of The Ramayana—a campaign that proved ambiguously successful. Valmiki, or Balmiki, soon became a new caste identity. Today there are temples dedicated to the literary saint across north India, though many Safai Karamcharis still privately pray to Lal Beg.

Two opposing ideologies about sanitation emerged within the independence movement. Following the lead of the Hindu right, M.K. Gandhi set up a special wing of the Indian National Congress, the Harijan Sevak Sangh, whose volunteers taught Dalits to sing Hindu devotional songs, urged them to give up liquor and beef, and warned them against Islam. (Gandhi popularized the condescending term “Harijan” for Dalits. It translates to “God’s Children.”) His agenda was doggedly opposed by Ambedkar, who argued that avarna communities needed their own political representation and that sanitation labor jatis had to be freed from their jajmani.

The conflict became bitter, even farcical, with Gandhi describing manual scavenging as a “sacred duty” that was purifying for Dalits, making a point to clean toilets himself at ashrams—saintly antics that Ambedkar saw through. “Under Hinduism scavenging was not a matter of choice, it was a matter of forced labor,” he wrote.

What does Gandhism do? It seeks to perpetuate this system by praising scavenging as the noblest service to society! Can there be a worse example of false propaganda than this attempt to perpetuate evils which have been deliberately imposed by one class over another?

Though Ambedkar drafted the Indian constitution, which contained important anticaste provisions, in practice the Indian National Congress would take a Gandhian approach to sanitation after independence.

In 1947 sanitation labor castes were at the center of one of the most morally repugnant episodes of Partition. The Indian and Pakistani governments had agreed to oversee population transfers, with Hindu and Sikh communities moving to India and Muslims to Pakistan. But as these migrations were still underway, Pakistan’s government passed the Essential Services Maintenance Act, which barred Hindu sanitation workers from moving to India—a decree that only Ambedkar had the courage to oppose. “Pakistan did not bother much if the Hindus left,” he wrote. “But who would do the dirty work of the scavengers, sweepers, the Bhangis and other despised castes if the untouchables left”? Over 35,000 Hindu sanitation workers were left behind as late as 1952. The psychologist Ashis Nandy later learned that “the Karachi elite and Pakistan’s political leadership had to cajole the Hindu Dalits to stay on in the city while ethnic cleansing was taking place all over.” Tellingly, Dalits were largely spared the violence of Partition, as the belligerents did not see them as true Hindus, Muslims, or Sikhs worth killing.

Sanitation was in a dire state when the British handed power over to the Congress. In 1954, the newly-formed National Water and Sanitation Program conducted its first major survey, finding that some 3 percent of citizens had access to a toilet with a sewage connection. Prime Minister Nehru promised to “improve health, education, and sanitation” alongside building up “a big productive machine,” but never turned these fine words into action. While the Congress claimed to represent all of India, the party was propped up by—and answered to—an elite coalition made up of the professional middle class, industrialists, and landlords, who, perversely, were extended subsidies and welfare measures that were largely denied to the rest of the population. When it came to sanitation, then, the colonial dichotomy held: “The middle class has been able to monopolize whatever basic sanitation services the state has provided,” Chaplin notes. This meant that most Indians still used dry latrines, which were cleaned by Dalits.

A number of commissions were set up to look into the “issue” of manual scavenging in these early decades. In Gandhian fashion, all said that Safai Karamcharis deserved better labor conditions, and none called for an end to their hereditary duty. In 1957 ₹984,000 were set aside to provide Safai Karamcharis with handcarts, in order to end the practice of “head loading”—carrying away excrement in a basket on one’s head—but only six hundred of 126,000 municipalities took part in the scheme. Then again, the entire blame should not be laid on the state. As Swaroop told me, there was “an absence of demand” for better sanitation access, because people were “happy with someone coming and taking away” their waste.

Omprakash Valmiki’s classic Hindi memoir Joothan (1997) offers a window into the social world of rural sanitation jatis in this period.9 The book opens in the 1950s in the state of Uttar Pradesh, in a village that is run by upper-caste Tyagis, who touch cows and buffaloes but not Chuhras like the author. Chuhras perform a number of tasks for Tyagis—cleaning their houses and outhouses, washing their cowsheds, disposing animal carcasses—for which they are paid in grain as well as leftover food. In an early scene, the headmaster pulls nine-year-old Omprakash out of class and takes him to the playground for a special lesson: “See that teak tree there? Go. Climb that tree. Break some twigs and make a broom. And sweep the whole school clean as a mirror. It is, after all, your family occupation.”

In 1983 the federal government convened a major conference at which it decided to install pour-flush latrines in all urban areas. (Low-cost models had been developed by a string of Gandhian reformers, including Bindeswhar Pathak, who in 1970 set up Sulabh International, a quixotic nonprofit focused on “the emancipation of scavengers.”) Sewage lines were thereafter gradually laid in towns and cities across the country, though access remains uneven. As of 2011, when the last national census was undertaken, over twenty million urban households were not connected to either a septic tank or a sewage line. The rural figures are still higher.

The current water-borne system is in some ways worse than the old dry latrines. Safai Karamcharis now enter sewer lines, which they unclog, and septic tanks, which they empty. A 2006 survey in Tamil Nadu found that sanitation workers were routinely exposed not only to excreta and contaminated water but also to blades and other sharp-edged objects.10 Over 680 ailments have been found to be prevalent among the workers, the most dangerous from noxious gases.

While elaborate workplace laws have been written to guard against such hazards, these are almost never followed, either by public or private employers. Workers thus routinely perish underground, nowhere more often than in the state of Tamil Nadu, which has reported the largest number of Safai Karamchari deaths over the past two decades. Since 2015, M. Palani Kumar has traveled across Tamil Nadu photographing the conditions in which Safai Karamchari work and live. Many of his images are of funeral processions, like a heartrending picture from 2019, which focuses on a three-year-old girl, Dhanushri, whose face is pressed against the glass walls of the freezer box in which her deceased father, Mari, is placed for the final rituals.

Being made to enter a septic tank or sewer line is akin to torture, as the Tamil writer Pandiyakannan makes clear in his autobiographical novel Salavaan (2008). Pandiyakannan is from the Kuravar community, an Adivasi group that was labeled a “criminal tribe” by the British, who pushed them out of their forested homeland, after which many began working in sanitation. His father was a Safai Karamchari employed by the Tamil Nadu government, and his mother did the same job on an informal basis. From childhood, he accompanied them to work. Long passages of Salavaan describe the task of cleaning septic tanks in meticulous detail:

Kumaran raked up the last two buckets of shit with his bare hands. He scraped the shit from the cistern walls and signaled for them to throw down the broom. Balan brought the broom from the bathroom and held it out for Kumaran. He couldn’t reach it. Balan gripped the broom between his toes and climbed down into the tank. He hung from the edges of the tank like he was doing pull-ups until Kumaran grabbed the broom.11

Many Safai Karamcharis have to drink before going underground. A 2017 survey found that 61 percent of sanitation workers in Maharashtra were habitual drinkers. “It is necessary for us to have alcohol before engaging in our work; otherwise it is not possible to work continuously,” one informant said.12

Over time, sanitation work split along gendered lines, as men tended to get hired as professional Safai Karamcharis, while women were left to clean dry latrines. Bhasha Singh gathers the testimonies of dozens of female sanitation workers from across India in her book Unseen, showing how the job is often passed down from mothers and mothers-in-law to daughters and daughters-in-law.13 Neera, a woman in Haryana who accompanied her mother to clean shit starting at the age of six, tells Singh: “My whole life has been spent like this. Now I am a grandmother. Even in my dreams I often see that we have received gloves.”

Until the 1990s, a number of factors combined to keep Safai Karamcharis politically marginal. In the first place, sanitation labor jatis have fewer numbers compared to others: political parties do not see them as a significant source of votes. Many are further isolated from local power structures as internal migrants: When sanitation work was being formalized during the colonial era, savarnas often refused to do the job, leading state authorities to relocate Dalits from other parts of the country to make up for the labor shortage. Methars from around Delhi were brought to work in the Telangana region, where their descendants still labor as Safai Karamcharis. Many of the sanitation workers in Mumbai are from Tamil Nadu. More bitter is their distance from Dalit political parties, which tend to be subordinated to the interests of more populous jatis.

Left to organize themselves, sanitation labor jatis have used different strategies to fight what Ambedkar described as the hydra of caste. The two leading advocacy groups—Safai Karmachari Andolan (SKA) and Navsarjan Trust (NST)—follow an agenda that might be termed abolitionist, in that they aim to free all Dalits from sanitation work and rehabilitate them to other professions.

The founder of the SKA, Bezwada Wilson, is an organic intellectual, as emerges from the affecting portrait of him drawn in Gita Ramaswamy’s book India Stinking.14 He was born in 1966 into a Christian Madiga household in Kolar, Karnataka, a factory town set up by the British in 1870 around a gold mine. By the 1960s Kolar housed 76,000 workers, most of them Tamil Dalits, who were in turn serviced by 236 community dry latrines, each cleaned by a separate Madiga Safai Karamchari, among them Wilson’s father and brother. The boy himself was protected from the job and sent away to college, after which he returned to serve the community as a pastor. One day in 1989, at twenty-three, he went to observe their work up close. The site of a man plunging his arms into a barrel of shit to retrieve a bucket was the turning point:

I lay on the ground by the side of the pit, and wept. I had no answers to the sight I saw, I wanted to die. I wept continuously…. I couldn’t eat, I couldn’t sleep. I had only two options: either I had to die, or I had to work to stop the practice. The first was easy, the second difficult. I told myself I would not achieve anything by dying.

Years later Wilson launched a campaign to end manual scavenging in Kolar. When the town’s mining officials did not relent, he got in touch with the Bangalore-based daily Deccan Herald, which published a report on the subject, leading parliamentarians and even ministers to demand a formal worksite investigation, as if they did not know perfectly well what was going on. In an emergency board meeting, the mining officials passed a resolution to install water-borne toilets and transition all Safai Karamcharis to other jobs. Wilson oversaw the process and then left to take the fight statewide. In 1993, when the federal government passed the Employment of Manual Scavengers and Construction of Dry Latrines (Prohibition) Act, which outlawed the use of dry latrines across India, a copy of the bill was sent to him for suggestions.

The NST’s founder, Martin Macwan, took up the cause of Safai Karamcharis later in his career, as Mari Marcel Thekaekara reports in her study Endless Filth.15 He was born in 1959 into a family of Christian Vankars, a Dalit jati in Gujarat whose traditional occupation is weaving. One of eleven siblings, he worked in the fields as a child but managed to make it through school and then university, where he got a law degree, though like Wilson he soon returned to serve the community. In 1996 he learned that female Safai Karamcharis in Ranpur, a village in rural Gujarat, had gone on strike to have their brooms replaced. “What totally devastated me was that they were not agitating against the practice,” he told Thekaekara. “They were merely begging the Panchayat to give them more brooms to prevent their hands from getting soiled with shit.”

When the 1993 act was implemented, all municipalities were assumed to be “free of manual scavenging” until proven otherwise by local magistrates, few of whom bothered to look into the filthy business. Groups like SKA and NST were left with the absurd task of finding the illegal dry latrines still in use everywhere. Volunteers conducted surveys across the country and presented the data in various court cases. (Macwan’s definitive 1998 report on the state of manual scavenging in Gujarat, “Lesser Humans: Scavengers of the Indian Republic,” lists six types of dry latrines cleaned by Dalits; one is simply a plot of land, bounded by a four-foot wall, where savarnas defecate.) Authorities in turn largely feigned ignorance or denied the evidence, as when a state lawyer claimed that photographs of head loading that NST submitted in court were fake. The plaintiff responded, “Navsarjan Trust will offer a gift of one lakh rupees to any person in the Court who is willing to pose for a photograph with a basket of human excrement on his head.”

The upshot of this government inaction was that SKA and NST grew in size and prominence. Hundreds of Safai Karamcharis joined the movement, burning their brooms and baskets. One of SKA’s most remarkable campaigns was a grassroots drive in 2004 to demolish community dry latrines in districts across Andhra Pradesh. The face of the campaign was an elderly woman named Narayanamma, whose lifelong job had been to clean the entire Buddapanagar women’s dry latrine complex in Anantapur, which had over six hundred users. While a group of local upper castes tried to protect the structure, she was able to make her way through the crowd—and strike the first blow against her old workplace—because of their refusal to come into contact with her. “Since I have spent my whole life picking up those people’s filth, neither would they touch me, nor would they want to be abused by me,” she told Bhasha Singh. “I knew them so well that I made untouchability my weapon.”

Savarna resistance to the liberation of sanitation laborers should not be underestimated. Like the Brahmins in Pālkuriki Sōmanātha’s parable of the god who took the form of a Madiga, they feel existentially threatened by the prospect of Dalits abandoning their hereditary duty. In Bihar, according to Singh, a Safai Karamchari started a small business, which upper castes promptly boycotted. “Trying to become a Brahmin by opening a tea stall,” they told her. “Who will drink tea made by a manual scavenger?” Such harassment makes Safai Karamcharis less confident about leaving the profession.

Macwan dwelled on this point when we spoke over video call. He told me a story to illustrate how Brahmanical ideology can be internalized by Dalits. NST once held a meeting at which sanitation workers were asked to name occupations they would like to take up. For two hours, they gave every possible reason—tradition, religion, ancestry—to explain why it was impossible to leave the profession. For a long time there was silence. Then one man suggested he might sell brooms. Another went further: he could sell brooms on a bicycle. Finally, after much prodding, a woman said she would like to knit and sell blouses—and was promptly shouted down by the men for stepping out of line.

Thanks to organizations like NST and SKA, most Indian states are now free of dry latrines. I asked Wilson over the phone if he felt any closer to the goal of emancipation than when he started out. Having made clear that upper-caste Hindus did not care about Dalit issues, he reflected that the needle has moved on sanitation, with other civil society groups, journalists, and even some politicians supporting the movement. Yet the biggest change was psychological. Sanitation labor castes no longer acquiesced to hereditary obligations, and upper castes no longer believed Dalits were born to clean their shit. “Today nobody can say that this is work [we] must do,” Wilson said. “When it comes to manual scavenging…somehow or other everyone thinks, ‘We must stop this.’”

The projects of abolition and labor organizing might seem incompatible. One seeks to free Dalits from sanitation work while the other tries to make the profession better for them. Yet the similarities between the two approaches are greater than their differences. SKA and NST are not opposed to waste work in the abstract; they are fighting to utterly transform how sanitation is practiced in India. Labor unions pursue the same goal when they agitate for better workplace protections, increased wages, and respect for employees.

Indian labor organizations took up the cause of sanitation workers as early as 1953, when the Prantiya Valmiki Mazdur Sangh, a local Safai Karamchari union, and the Communist Party of India led a joint campaign to demand better wages and benefits for sanitation laborers employed by the Delhi Municipal Corporation. Their march into the municipal headquarters ended in mass arrests. In 1957 ten Safai Karamcharis in Mumbai held a hunger strike for improved working conditions such as medical facilities, housing, and the removal of upper-caste supervisors. Nehru explained why the state would not negotiate: “A public utility or public service affected the community directly and could not be judged from the same point of view as an industrial strike.”

The state’s attitude in this and other instances was programmatically casteist. Sanitation was viewed not as a profession but a “public service”—something Dalits were born to do. How far the state would go to protect caste structures was made clear in 1996, when Nagarpalika Karamchari Sangh, a union of sanitation workers, held an eighty-day statewide strike in Haryana demanding timely pay. The BJP-led state government cited the Essential Services Maintenance Act—a 1968 law that prohibits strikes in essential sectors—to fire six thousand Safai Karamcharis and jail some seven hundred more for up to seventy days. Volunteers from the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh, the umbrella organization which oversees the BJP, showed up with brooms to help the government in its time of need. They suffered the task for two whole days, after which Safai Karamcharis were dragged out of their homes and forced back to work.

A major challenge facing sanitation unions today is labor informalization, a process set in motion in the early 1990s, when the state gradually rolled back public sector investment and invited private companies to take over services like sanitation. Workers were then separated into two tiers—full-time employees on the state payroll and contract laborers hired by private third parties—whose workplace conditions diverged starkly. Today, in Mumbai, Safai Karamcharis employed by the Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation are paid ₹9,000 (a little over $100) a month, while those roped in by contractors earn as little as ₹4,000, and are further deprived of pensions, insurance, and sick leave. To avoid labor laws that apply to businesses that employ twenty workers or more, contractors hire crews of eighteen, which are assigned to different neighborhoods. In some places Safai Karamcharis have even been reclassified as “volunteers” who receive an “honorarium.”

No union has been as successful at combating informalization as the Kachra Vahtuk Shramik Sangh, which represents seven thousand of the eight thousand contract sanitation workers employed in Mumbai. KVSS began by fighting for better workplace conditions: initially Safai Karamcharis were not given raincoats, or attendance cards, or minimum wage, or holidays—they worked 365 days a year. It has filed hundreds of cases exposing illegalities in the contract system and fought to reclassify contract workers as full-time employees. In a major 2003 settlement, 1,200 contract workers were made permanent; eleven years later, after another drawn-out lawsuit, another 2,700 followed. “The group that has been made permanent is separated from the rest,” the union’s founder, Milind Ranade, told me over video call. “This is how they try to chop you into pieces…. For every new batch, you have to fight from the beginning.”

While Ranade came to sanitation work as an outsider, Raees Mohammed grew up with an intimate knowledge of the profession. His father was a sanitation worker on the Tamil Nadu government’s payroll; his mother was a sweeper at a school. The first member of his family to receive higher education, Raees did research on Safai Karamcharis across India for his Ph.D., but turned down a career in academia for sanitation, returning to Kotagiri, in rural Tamil Nadu, to found the Nilgiris All India Sanitation Workers Self Respect Trade Union. Raees told me over the phone that most Safai Karamcharis there are contract workers. Without an office, they stand outside the municipal office all day, riding from job to job on the flatbeds of garbage trucks, even during the monsoons—practices the union has successfully overturned. “My idea was never about salaries,” Raees told me. He is focused on inculcating self-respect among sanitation workers. The problem in India, he said, “is that labor does not have value. Only caste has some value.”

One obvious way to make sanitation work safer is to have machines do it. Any number of machines can be used to unclog sewage lines and drain septic tanks. Even rudimentary tools could make a significant difference. Raees told me that Safai Karamcharis in Kotagiri have to pick up sanitary pads and condoms from clogged toilets with their bare hands. While a fiberglass measuring pipe is used in other countries to check the waste levels in septic tanks, workers in his union use sticks. Technology in India is “pre-development,” he said.

Promises about “mechanizing” the industry have been made and broken for decades. Most prominently, in 2013 the Congress government passed the Prohibition of Employment as Manual Scavengers and Their Rehabilitation Act, which made it illegal for Safai Karamcharis to be sent into septic tanks. (Sewer lines were miraculously deemed safe.) Because no effort was made to procure, let alone produce, the machines that were supposed to perform this task, Safai Karamcharis kept going underground. More perniciously still, some municipalities have modernized only those parts of the sewage system that do not involve sanitation workers. In Ahmedabad, the scholar Stephanie Tam notes, “Biased sewerage development has resulted in sewage treatment plants and pumping stations whose current sophistication rivals those in most Western cities, while maintenance technology has not progressed beyond buckets and human hands.”16

In 2014, the year he came to power, Narendra Modi launched a flagship development project called the Swachh Bharat Abhiyan (SBM), or Clean India Mission, with the ostensible aim of eliminating open defecation in rural India. The focus was on building toilets, which the government did with religious fervor, pouring some ₹6.6 billion into construction by 2021. A major publicity campaign was launched to advertise the scheme, with politicians and Bollywood celebrities like Akshay Kumar appearing on television with brooms. Modi himself washed the feet of Safai Karamcharis, in a ghastly replay of Gandhian uplift. Districts were given cash prizes for going “open defecation–free.”

Chalking SBM up as a tremendous success, the government released figures suggesting that rural households with access to sanitation went up from 38.7 percent in 2014 to 81.7 in 2018—a claim with no basis in reality. Thousands of toilets were indeed built under the SBM, yet many go unused, largely because construction was shoddy and often incomplete, with vast amounts of money lost to corruption. Moreover, since most villages remain unconnected to state sewage lines, toilets are attached to septic tanks, which Safai Karamcharis are forced to manually empty. In a recent paper, the economist Kazuko Motohashi argues that the SBM’s overall impact has, if anything, been negative: due to poor waste treatment, the policy has led to an estimated 72 percent rise in river pollution.17

Better technological solutions have come from within the Dalit community and not received federal support. In 2017, in collaboration with the Dalit Indian Chamber of Commerce & Industry (DICCI), the Hyderabad Metropolitan Water Supply and Sewerage Board acquired seventy “mini sewer-jetting machines” that use water to unclog sewer lines. These machines, 130 of which are now in use in the city, are owned by Safai Karamcharis, who are given state loans to make the purchase. The notion that they can all become “sani-entrepreneurs,” as claimed by the DICCI, is risible: fewer than fifty of the city’s 1,800 Safai Karamcharis have managed to make the switch. Nor does the program delink caste and sanitation work. Yet the basic goal of ending manual scavenging has largely been accomplished. Machines clean almost all drains in the city.

Perhaps the most remarkable technological intervention has been made by Kennithraj Anbu. An engineer based in Chennai, he found his calling in second grade, on seeing his father lower himself into a manhole for the first time. The pain of discovering what a Safai Karamchari’s job entails stayed with him through college. Though he was hired by a multinational robotics firm on the strength of a prize-winning paper, he quit the lucrative job and in 2018 founded a startup called Transen Dynamics. The company soon developed a cheap, easy-to-use gas detector that sanitation workers can lower into sewers to find out whether a manhole is safe to enter.

I asked Anbu if he had faced caste discrimination working in the field of technology, which is notoriously dominated by Brahmins. His answer was more nuanced. Brahmanism, he told me, shaped the very kinds of research produced in India, where theoretical fields are valued over anything merely practical. Colleagues were dismayed when he shared his idea for a gas detector, worrying it would lead to his branding as a “manual scavenging scientist.” Investors stayed away from the project, and the Chennai municipality argued that gas detectors were unnecessary since manual scavenging had been abolished. But when Anbu was featured on a popular Tamil television show, many investors got in touch (although they wanted him to design a machine for any sector other than sanitation), and the state government has shown interest in procuring Transen’s gas detectors. “We are ready to give our knowledge to the government” for free, he said.

Organizing by sanitation workers has taken a more winding course in Pakistan, where caste and religious bigotry go hand in hand. Most Safai Karamcharis there are Christians from the Chuhra jati, a sanitation labor caste once found across undivided Punjab. In the late nineteenth century thousands of Chuhras converted to Christianity, which brought them greater dignity even as they failed to escape waste work. Their leader, S. P. Singha, chose to join Pakistan at Partition, thinking that Muslims, as fellow people of the book, would make better neighbors than Hindus.

Alas, Singha was proven wrong. Like Pakistan’s other minorities, Chuhras have been locked out of state institutions and subjected to majoritarian harassment: forced conversions, blasphemy charges, assaults. Evicted from rural areas, where land was given to Muslim refugees from India, they now mainly reside in segregated urban ghettoes. “The stigma of their caste origins and the related extreme vulnerability still plagues the Christian community,” the historian Charles Amjad-Ali notes. “This in spite of Islam’s theological denial of these inequalities as part of the ideal faith claim.”18

The experience of Chuhras in Pakistan raises perplexing questions about the persistence of caste hierarchies after religious conversion. On the one hand, Islam is certainly a more egalitarian religion than Hinduism, lacking the latter’s baroque system of taboos: who to touch and not to touch, where to eat and not to eat, what work to do and not do. This is why, for instance, Raees converted and dropped his given Hindu name. “Mosques have toilets within their premises,” he has said. “A toilet is not considered unholy.” On the other hand, untouchability is still practiced toward Safai Karamcharis in Pakistan, where, as the scholar Faisal Devji has noted, it is often described as religious rather than caste discrimination.

Chuhras are synonymous with sanitation in Pakistan, making up less than 2 percent of the population but 80 percent of Safai Karamcharis. This is in part because sanitation jobs were long semi-officially reserved for Christians, as Muslims felt the work was defiling. As late as 2013 the chief minister of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province could tell journalists that “only non-Muslims would be hired as sweepers.” On Easter Day in 2014 and 2015, notices were put up asking citizens to please throw their waste in trash cans, as the Christian community was on holiday. In Lahore, seventy people died on the job in 2019 alone.

Mary James Gill, a former state parliamentarian and herself from a Chuhra background, publicly took up the community’s cause after the death of Irfan Masih—the Safai Karamchari three Muslim doctors refused to treat in 2017. That year, during the state budget proceedings, she gave a speech about untouchability against Christians, a practice other politicians still deny, and launched an online campaign called “Sweepers Are Superheroes” to bring visibility to sanitation workers, who are largely overlooked in the Pakistani press. The campaign’s largest success has come from appealing to Islamic principles such as the dignity of labor. “When we argue on the basis of Islam, it makes sense to them,” Gill told me. “They say it’s a bad practice we have inherited from Hinduism.” Soon after the campaign was launched, sanitation workers received an outpouring of support from Christians and Muslims alike, leading more workers to embrace their identity. There is now a Sweepers’ Association of Pakistan which organizes in over twenty-two cities. Meanwhile, like Dalits in India, Chuhras remain frequent targets of mob violence, usually prompted by charges of blasphemy: eight churches were burned down by fundamentalists last week.

Since the onslaught of the pandemic, India’s sanitation workers have been forced to labor in conditions even more dangerous than usual. In photographs that M. Palani Kumar shot during the lockdown in 2020, they are seen cleaning the deserted streets of Chennai. Rather than address workplace grievances, the government made sanitation into a spectacle, as state officials publicly garlanded Safai Karamcharis, who were now called “corona warriors.” On May 3, 2023, military planes performed maneuvers in the sky to thank them. Joel Lee and Kanthi Swaroop rightly criticize these empty gestures as “Gandhian,” although they have also noted a more promising development: many sanitation workers said that municipalities and contractors had begun to pay wages on time.19

SKA did not allow the pandemic to halt its most ambitious mobilization yet. Launched in May 9, 2022, “Stop Killing Us” is an ongoing series of daily protests in towns and cities across the country. Groups of sanitation workers and activists—numbering anywhere from under a dozen to over a hundred people—gather, holding up signs with the campaign’s title and a large portrait of Ambedkar, to publicly shame the nation about the ongoing deaths and reiterate their demands for rehabilitation. “I said it is seventy five years of independence, so at least we will do the protests seventy five days,” Wilson told me. But even after the seventy-fifth day, there was enthusiasm for the campaign, which took on a life of its own. “Now the Safai Karmachari Andolan is not organizing anything,” he said. “The movement has gone into the hands of the people… We are only giving a calendar.”

Sanitation labor castes made the news for other reasons during the pandemic. On September 14, 2020, four upper-caste Thakur thugs assaulted and gang-raped a nineteen-year-old woman from the Valmiki community in Hathras, Uttar Pradesh. She later died from her injuries. The police burned the victim’s body at a hidden location, which overrode the family’s request for a public funeral. Dalit groups across the country mobilized to protest the atrocity; garbage piled up in several cities as Safai Karamcharis went on strike. The next month, more than thirty thousand people in seven states took part in a commemoration organized by Macwan’s nonprofit Dalit Foundation. People were invited to apply turmeric to an image of the victim, a mourning ritual. Women from the Valmiki community were “weeping as if they were putting the mark on a photo of their own daughter,” Macwan told me. In April three of the four alleged killers were acquitted.

Savarna writers like myself have long expressed a dubious fascination with sanitation. During the independence movement, poets and novelists treated Safai Karamcharis less as characters than as screens on which to project confusion and guilt. Rabindranath Tagore, the founding figure of modern Bengali literature, composed (or, in some cases, translated from Bengali) a series of English poems about the plight of manual scavengers for early issues of Gandhi’s journal Harijan. “Sweet Mercy” is worth quoting in its entirety.

Raidas, the sweeper, was tanner by caste

whose touch was shunned by the wayfarers

and the crowded streets were lonely for him.Master Ramananda was walking to the temple

after his morning bath,

when Raidas bowed himself down before him from a distance.“Who are you, my friend” asked the great Brahmin

and the answer came,

“I am mere dust dry and barren,

trodden down by the despising days and nights.

Thou, my Master, art a cloud on the far away sky.

If sweet mercy be showered from thee

upon the lowly earth,

the dumb dust will cry out in ecstasy of flowers.”Master took him to his breast

pouring on him his lavish love

which made a storm of songs

to burst across the heart

of Raidas, the sweeper.

Fictional texts likewise display a strange mixture of good intentions, condescension, injudiciousness, and presumption, with novelists too easily slipping into the perspective of Safai Karamcharis (or “sweepers,” as they were called then). Thus Mulk Raj Anand, in his famous 1935 English novel Untouchable, offers a serene description of the labor the hero, an eighteen-year-old sweeper named Bakha, performs in a British army cantonment:

He worked away earnestly, quickly, without loss of effort. Brisk, yet steady, his capacity for active application to the task he had in hand seemed to flow like constant water from a natural spring…. As he rushed along with considerable skill and alacrity from one doorless latrine to another, cleaning, brushing, pouring phenoil, he seemed as easy as a wave sailing away on a deep-bedded river.

In the course of a day, Bakha goes from one humiliation to the next—he is harassed by a mob for accidentally touching and so polluting an upper-caste man; his sister is sexually abused by the local priest; his father throws him out of the house for missing one shift at work—only to find solace in a speech from a bespectacled visiting politician by the name of Gandhi, who discusses the need to abolish untouchability.

Then again, at least these savarna writers felt compelled to address sanitation, unlike their successors in the independent era, who have not produced a single notable novel on the subject, nor for that matter on caste. Serious engagement has been left to journalism and scholarship, though here too the results are uneven. Newspaper reporting is too often reduced to bare summary—so many deaths; so many responses from government officials—and academic research is too often focused on proposing technocratic solutions.

Two savarna writers who have risen to the ethical challenge in nonfiction are Bhasha Singh and Gita Ramaswamy. Both came to the subject by chance, with little prior knowledge or even basic awareness. In the introduction to Unseen, Singh recalls using dry latrines as a child in a poorer relative’s home, never once pausing to wonder who cleaned up: “Just like me, those people who have such dry latrines in their homes have probably never even given a thought to the person picking up the excrement.” Much later, now a veteran journalist in her thirties, she was introduced to a group of female manual scavengers by a feminist and leftist activist. Initially she “regarded it as just one story among the many other stories I was working on.” But eventually the meeting led her, with the help of guides like Macwan and Wilson, to learn as much as she could about their struggles. Singh later joined the Safai Karmachari Andolan.

A publisher, social activist, and former Communist militant, Ramaswamy has been involved in Dalit movement for decades. For two years starting in 1978 she tutored school children among Safai Karamcharis in the Ghaziabad district of Andhra Pradesh, but even then the moral implications of how sanitation work is assigned did not truly strike her. “I would watch the women return every day at noon with head-loads of shit that they would empty in the open field in front of their colony,” she recalls. “It shames me now to write that apart from worrying whether I would get tapeworms from the pork I ate daily in their houses (the pigs fed off the shit that was dumped in the field), I did not think twice about their work and its nature.” Meeting Wilson and other SKA members in 2001 made her realize that “I was like every other privileged caste Hindu in society—complicit in getting manual scavengers to clean shit by simply being ‘unaware’ of it.” India Stinking is offered as penance.

Both books are driven by anger toward savarnas who uphold the caste system and admiration for—and solidarity with—those seeking to end it, primarily Safai Karamcharis. Shame and self-denunciation, while inevitable, are kept to a minimum, with much of the space given over to the stories of workers and political analysis aimed at rousing savarnas from their amoral stupor. Singh and Ramaswamy strive to disavow their own caste privilege and complicity, even as they know full well that they can never do so completely. They speak, in other words, on behalf of the abstraction “civil society” and denounce other abstractions like “Hinduism” and “the caste system.”

Yet that leaves a fundamental question. How to come to terms with the fact that Dalits live and die amid savarna waste? The philosopher Gopal Guru clarifies the true stakes of the matter in his essay “Archaeology of Untouchability,” which argues that untouchability is not a response to something exterior but rather a practice developed by savarnas to deal with the troubling awareness of their own corporeal filth.20 “All organic bodies contain within them negative properties such as sweat, excreta, urine, mucus, and gases,” he writes. “The organic body as the source of impurities suggests a kind of ontological equality—that every body is dirty, both in a moral sense as well as a material sense.” Unwilling to accept their own corporeality, savarnas have outsourced filth onto Dalits, who are forced to physically take away the waste savarnas produce, as well as to serve as symbolic dumping grounds for the contamination they sense in and around them. Guru quotes the anticaste intellectual Vitthal Ramji Shinde: “Untouchability is a kind of repulsive feeling, a sort of nausea, that sits deep at the bottom of the Brahmanical mind.”

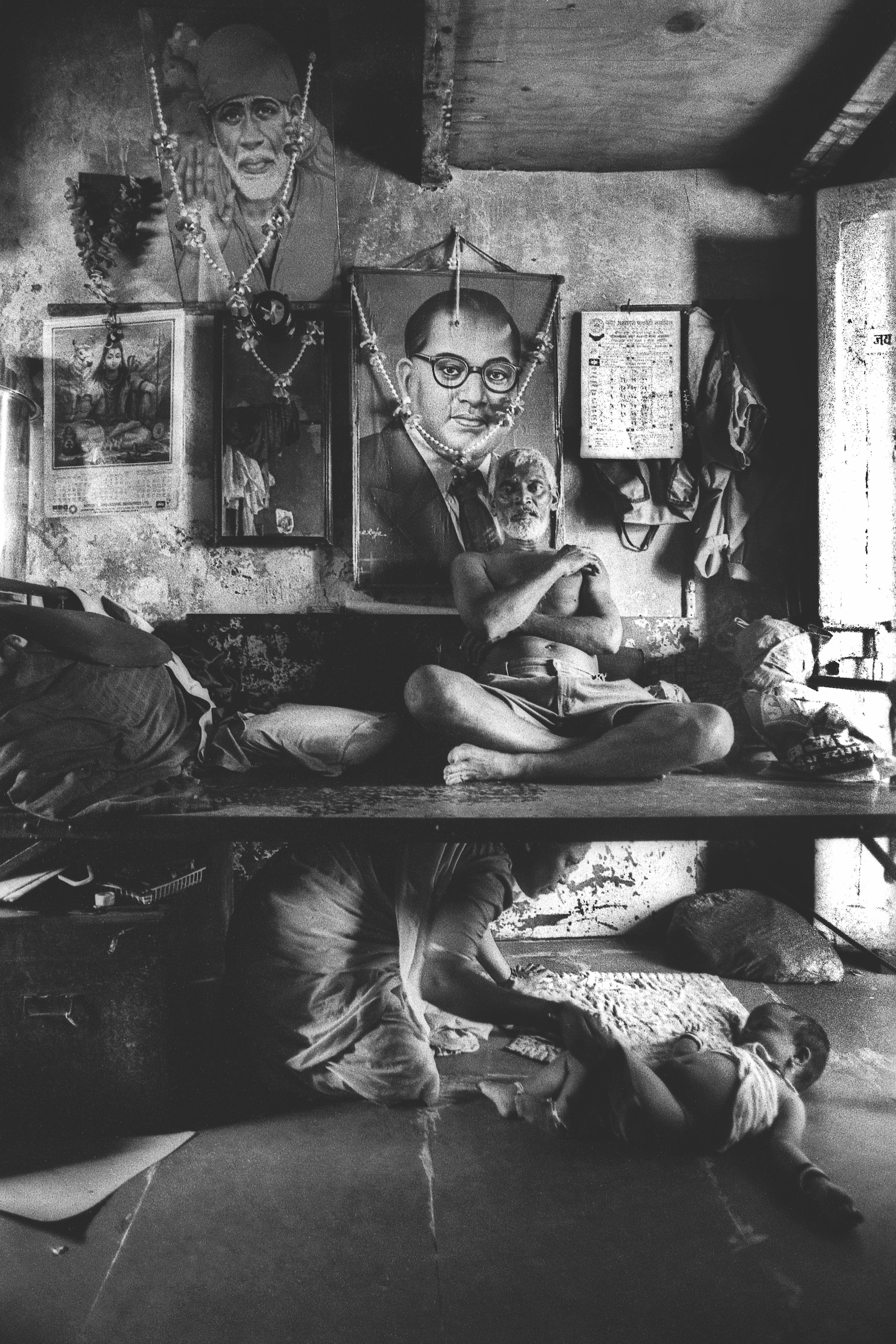

One of the rare interiors that Sudharak Olwe photographed is set in the home of a Safai Karamchari family. From close to the ground, Olwe’s lens surveys what seems to be the main—perhaps, the only—room, where a thin wooden cot is pushed up against the wall. Bare-chested, the Safai Karamchari sits on the cot, beside a rolled-up mattress and pillows, while below, on the floor a woman, presumably his wife, plays with an infant child. Few pictures hang on the wall: a calendar illustrated with a Hindu deity; a portrait of the godman Shirdi Sai Baba; and another far larger portrait, this one framed and garlanded, of Ambedkar. Together the forefather of the Dalit movement and his anonymous disciple look out at the viewer, from the past and the present, posing questions to which we had no answers then and have no answers now.