In our May 9 issue, Darryl Pinckney reviews an extensive survey of “the Harlem Renaissance and Transatlantic Modernism” at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. “If anything,” he writes, “the exhibition liberates the individual African American artist. It says how eclectic the past is in its artistic practices and styles.” Pinckney’s review offers a tour of those styles: “splendid, delicate likenesses of Alain Locke and Langston Hughes” by Winold Reiss; a “hallucinatory male nude” by Beauford Delaney; the “stylized and angular” figures of Aaron Douglas; the “formally inventive genre scenes” of Archibald Motley.

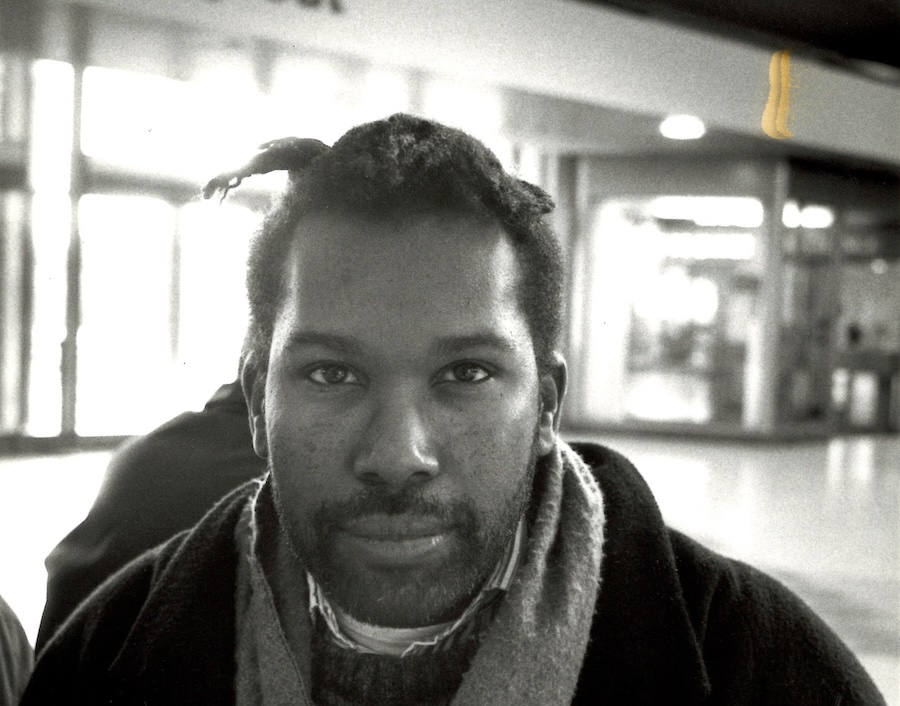

Since his first contribution in 1977, Pinckney has written more than a hundred essays for the Review, including on a number of figures associated with the Harlem Renaissance—Hughes, Zora Neale Hurston, Claude McKay, Nella Larsen, Countee Cullen—and on the history of the neighborhood itself. “Harlem exported its tempo, its attitude,” he wrote in 1982, “and helped make Manhattan the capital of the twentieth century.” Among his other subjects have been the election of Barack Obama, “Princess Margaret and her scandals,” Eighties novels “written from the inside of youth,” and the life and work of James Baldwin. He is the author of two novels and four books of nonfiction, most recently Come Back in September (2022), a memoir of his years working at the Review and his friendship with Elizabeth Hardwick.

We e-mailed about the Metropolitan exhibition, the centenary days of HBCUs, and why “Toni Morrison didn’t capitalize black.”

Daniel Drake: You open your review with a survey of contemporaneous writing about the Harlem Renaissance. Why do you think writers like James Weldon Johnson and Alain Locke were so “reserved,” as you put it, in their assessments of the visual art coming out of that period, when they were otherwise quite effusive about the literary, political, and cultural production in black New York?

Darryl Pinckney: Johnson and Locke were writing about African American art at what was the start of the careers of most of the artists in the Harlem Renaissance exhibition. There was not as yet much to see of their work. Artists like the sculptor Richmond Barthé went on working for decades, and he lived outside New York in those years. Meta Warrick Fuller belonged to an older generation, as did Augusta Savage. Then, too, the Harlem Renaissance itself was a brief period, little more than a decade, from 1919 to 1931. Was it David Levering Lewis and Jervis Anderson in their histories who date its beginning from James Reese Europe’s band and its first performances in France, with the black soldiers who were in no hurry to come back to the US? Someone else—I forget who—said that the New Negro movement began earlier, with the black boxer Jack Johnson. His victories got films of his bouts banned in the US under interstate commerce laws.

For Langston Hughes, the Harlem Renaissance began with the new music, with the Eubie Blake and Noble Sissle musical of 1921, Shuffle Along. For him, the Harlem Renaissance ended after the stock market crash. He says the party stopped with the funeral of A’Lelia Walker in 1931. That was also the year black gangsters lost control of the numbers racket in Harlem. Gilbert Osofsky in his study from 1963, Harlem: The Making of a Ghetto, tells the story of Harlem’s development that Johnson does not. It was overcrowded and poor from the get-go, which was why figures such as the poet Sterling Brown bitterly asserted that the Harlem Renaissance had little to do with or to offer most African Americans. Brown pointed out that more books by African American authors were published in the 1930s than in the 1920s—Zora Neale Hurston’s among them. But several writers of the Harlem Renaissance could not sustain careers during the Depression. George Wylie Henderson, for example, faded away after having published two novels.

For me, the exhibition took me back to tours of Historic Black Colleges and Universities I made with my parents in the late 1960s and early 1970s, the centenary days of many of these institutions, to the libraries, administration buildings, chapels, and galleries that had murals on themes of Negro histories and portrait after portrait of outstanding personalities. As a teenager I went around somewhat wearied by the duty of the visits. Seeing this kind of art again, gathered together, was like a reproach, but also yet another chance to appreciate what I’d failed to early on.

The whole thing was a discovery. Not all of it would be what anyone would call great art, but that is not the point here. However, an earlier Met exhibition that intended to give Juan de Pareja his due did him little favor. The aim was to show that he was more than a bondsman to Velázquez, which Velázquez clearly understood, given the training he afforded de Pareja. De Pareja was an accomplished painter; but Velázquez had genius, and placing their work side-by-side made the difference dramatic.

Were there any artists or works that you had to cut from your review, or couldn’t fit in the first place, that you think still merit some attention?

Of course there is too much for one exhibition to cover. Graphic art, posters, the music, and so on. It was primarily a literary movement, to start with anyway. By the way, I misattributed a still life in my notes, which led me to say, incorrectly, that Lois Mailou Jones was not included in the exhibition.

I was struck by your observation that representational art predominates over “the purely abstract” at the exhibition, and, perhaps by extension, in the Harlem Renaissance. Why do you think this was the case?

Much American art after the rise of the abstract expressionists was regarded as slightly old-fashioned and out of it, and I remember discussions in which the abstract was promoted as a way for African Americans to escape what were thought of as the burdens of the representational. As if African American history were a limitation. These days a black figure—don’t capitalize me; Toni Morrison didn’t capitalize black; to do so inscribes further the very otherness we’re supposed to be getting rid of—immediately dignifies a work or gives it a meaning it perhaps has not really earned.

What writing are you working on currently?

I am trying to trace the history of my family during slavery and to write about this journey in the archives. One of the awful things about the Pinckneys of South Carolina is that they were such good businesspeople that they kept detailed records and ledgers, and so I have many clues because my ancestors were considered property. I read an article that ended with a chilling line about how those who declined to take the master’s name can no longer be traced. But two Easters ago I met in Beaufort, South Carolina, a white Pinckney for the first time and was disturbed that I was not disturbed by how much I liked her. My trainer said he would have slugged her. She was ninety-four years old at the time. Then someone I respect a great deal revealed that his mother is a Pinckney, so there you go.