Ninety-five percent of Sudan’s total grain production occurs in November and December. It should be a time of plenty. In the southeastern state of Blue Nile, farmers fashion conical gourds into wazza, horn instruments with a bright clear sound, which they play to celebrate the harvest season. Last year they were silent.

In April 2023 a war broke out between the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) and the Rapid Support Forces (RSF), the major factions of Sudan’s ruling military junta. The conflict has created a humanitarian catastrophe. In January the UN published a report claiming that during the first eight months of the war, between 10,000 and 15,000 people were killed just in El Geneina, the capital of West Darfur state; no one knows how many have died overall. Over a million people have fled abroad. Ten million are internally displaced, more than in any other country.

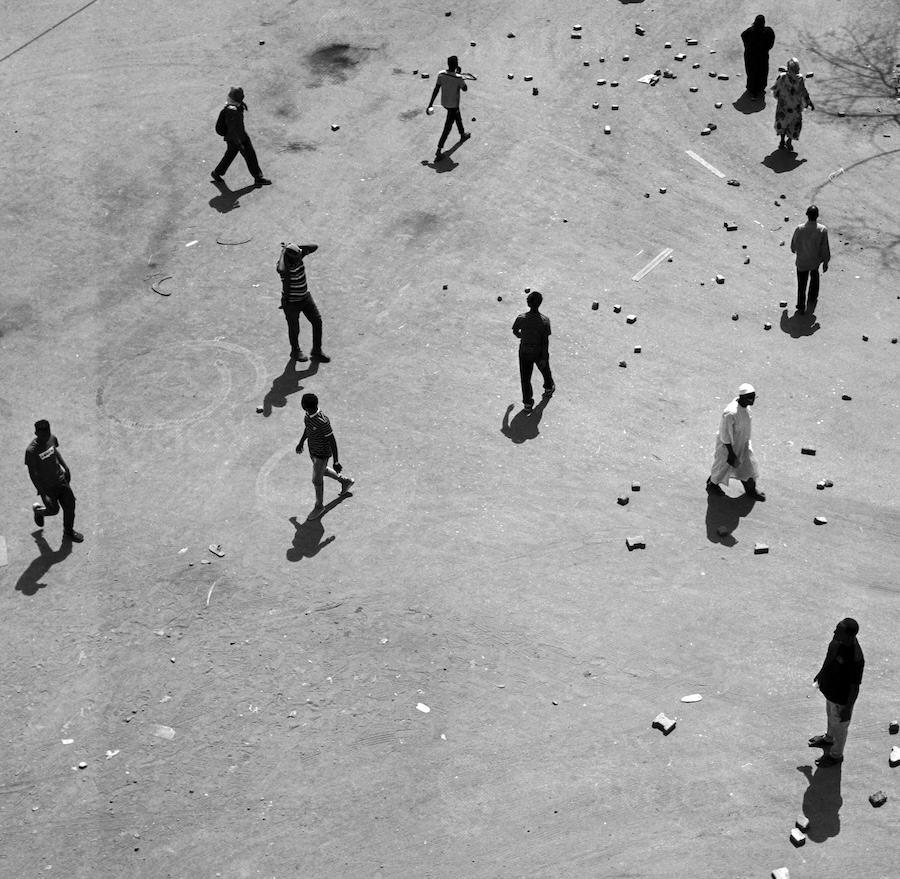

The belligerents have targeted residential buildings, humanitarian resources, banks, and government ministries. They have also disrupted agriculture. Both sides have pillaged farms and destroyed crucial infrastructure, including 75 percent of flour-milling capacity.

Parts of the country are now in famine. Over fifteen million Sudanese people were already acutely food insecure before the war began. Hunger has drastically increased since then, in part because of the fall in grain production, which during the 2023–2024 harvest season was 46 percent below that of the previous year—a shortfall estimated at 3.7 million tons.

As of October 2023, the Integrated Food Security Phase Classification (IPC), a global monitoring agency, claimed that nearly eighteen million people, almost 40 percent of the population, faced acute hunger. Those figures were calculated before the extent of the last harvest’s failure was known. Last month the Clingendael Institute, a Dutch think tank, released a report suggesting that 2.5 million people will die from famine-related causes by the end of September. Sudan is experiencing the largest famine the world has seen for at least forty years.

Addressing a famine of this magnitude would require an enormous buildup of humanitarian aid, which prior to the war constituted only a tiny part of the Sudanese food system. In 2022 the UN’s food agency, the World Food Programme (WFP), supplied the grain needs of 4 percent of the population. Expanding food assistance at this scale is not impossible: the WFP did it in 2021 after the fall of Kabul. But in Afghanistan the humanitarian appeal was fully funded by international donors. The picture in Sudan is bleaker.

Over fifty million acutely food insecure people live in the Horn of Africa, but the region receives a fraction of the funding the UN requests, in contrast to Ukraine, whose appeals are consistently overfunded. In mid-April, at a donor conference in Paris, Western governments pledged $2 billion for relief in Sudan. That seems impressive, but it meets only half the UN’s appeal—and so far only $468 million has come through.

There are other challenges. The UN regards the SAF as Sudan’s legitimate government and seeks its authorization for all aid delivery; it fears being thrown out of the country otherwise. The SAF has taken advantage of this arrangement to channel aid to the territories it controls, which mainly lie in the north and east, while largely preventing deliveries to RSF-held areas, which include almost all of Darfur in the west and a broad swathe running through West Kordofan to Gezira state in the center. (A patchwork of other armed groups also hold territory.) This siege has been especially devastating because the RSF controls some of the most severely food insecure regions, including much of Darfur.

The war began in the capital, Khartoum; as of this writing, fighting there continues. The SAF has relocated its administrative capital to Port Sudan in the northeast, which is where UN agencies are now based. At the edge of the Red Sea, their convoys wait weeks for travel permissions from the Humanitarian Aid Commission (HAC), which the government set up in the 1980s to control aid delivery. Sometimes the HAC demands five different stamps for an aid convoy to travel outside Port Sudan; often requests aren’t denied but tossed into a black hole of non-response.

In the first ten months of the war some NGOs were able to transport aid across the western border with Chad, which is almost entirely held by the RSF. But this past March the SAF declared that it would only allow aid to enter through its border crossings, effectively denying cross-border movement from Chad altogether. The UN complied, with catastrophic results for Darfur. Conflict and looting reduced harvest yields by as much as 8o percent compared to the previous year. In March an IPC alert showed areas with emergency levels of food insecurity across Darfur’s four states. A WFP spokesperson told us that the famine threshold has not been met, but indicated that 2.6 million people are at high risk of catastrophic levels of food insecurity, and that “we could be seeing famine-like conditions across the country.” However, another WFP official, who asked to remain anonymous, said that the UN agency has internally assessed that parts of Darfur are already in famine. In Kalma, an Internally Displaced People (IDP) camp in South Darfur, the aid group Alight reports that four children die each day from malnutrition and related issues, such as diseases caused by weakened immune systems. Humanitarians in Chad told us that Sudanese refugees are fleeing not conflict but hunger.

The RSF has its own predatory apparatus for controlling aid. Last August its leader, Mohammed Hamdan Daglo (commonly known by the nickname “Hemetti”), formed the Sudan Agency for Relief and Humanitarian Operations (SARHO), a version of the HAC. The RSF has greatly profited from aid delivery: in West Darfur it charges aid workers exorbitant checkpoint fees and forces them to use its trucking companies. Like the SAF, the RSF prevents aid deliveries to enemy-held territory. In March it commandeered the goods on a humanitarian convoy headed to El Fasher, the one city in Darfur not yet under its control. The same month it confiscated WFP food aid heading to the Ronga Tas IDP camp in Central Darfur, sharing the loot among its soldiers and refugees at an RSF-run IDP camp nearby.

The belligerents have thus ensured that most Sudanese people are cut off from lifesaving aid. WFP’s Executive Director, Cindy McCain, has stated that the organization is able to deliver food to only 10 percent of the population facing emergency levels of food insecurity. The UN’s relief chief, Martin Griffiths, has said in an internal note to the Security Council that the other 90 percent are out of reach.

Sudan is no stranger to war or hunger. Since independence in 1956 there have been three civil wars and at least five famines—the number is contested. In 1988–89, during the second civil war (1983–2005), government-aligned militias rampaged through the southern state of Bahr el Ghazal, poisoning wells, killing farmers, and razing fields in areas held by the rebel movement, the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement/Army (SPLM/A). Half a million people are thought to have died. In 2003–2005, during the conflict in Darfur, state-backed Arab militias known as the Janjaweed (the precursors to the RSF) targeted non-Arab communities, killing over 30,000, displacing millions, and disrupting agricultural cycles, which resulted in a further 200,000 deaths from hunger, disease, and exposure.

These famines, like the wars that triggered them, were localized. Today, hunger and fighting has spread over almost the entire country. Faced with a tragedy of such proportions, it is understandable to focus on pressing challenges like delivering more aid and brokering a cease-fire. But no amount of aid will fix the structural issues underlying Sudan’s chronic food insecurity, and in the absence of major political realignments, a cease-fire is unlikely to bring lasting peace. Understanding the origins of Sudan’s present crisis requires returning to its postcolonial history.

Hunger is not experienced equally across Sudan but gnaws its way through a landscape marked by exploitation and inequality. Since independence, a narrow coterie of Arab elites based in the Nile Valley have controlled the state. Rather than implement policies to equitably develop the country, they have captured government institutions and used them to enrich Sudan’s riparian urban centers (such as Khartoum and its sister cities of Omdurman and Bahri) at the expense of its peripheries (such as Blue Nile, South Kordofan, and Darfur).

This divide is reflected in Sudan’s food system. As the scholars Magdi El Gizouli and Edward Thomas have shown, the country is split between wheat eaters in the urban centers and sorghum and millet eaters in the peripheries. Wheat is mostly imported; its price can soar during global food price spikes. Sorghum and millet are grown locally; their availability is vulnerable to climactic shocks and conflict. To placate the urban centers, successive regimes have imported and subsidized wheat and bread—subsidies that do not reach rural areas. They have raised the necessary foreign currency by exporting primary resources from the peripheries, such as grains, livestock, gum arabic, oil, and gold. This is the transmutation that turns sorghum into wheat; it’s a magic trick that exploits rural Sudan.

The dual food system had its origins in postcolonial agricultural policy. On the eve of independence, much of the population was engaged in subsistence agriculture, and a significant number were pastoralists. In the 1960s the government secured credit from the Gulf states and the World Bank to create mechanized agricultural projects in Sudan’s southeast, between Ethiopia and the Nile. These schemes produced sorghum for internal consumption and sesame for export.

In 1969 Gafaar Nimeiri took power in a coup, suspending the constitution and banning the Muslim Brotherhood, which he considered a threat to his power. He pushed a scheme to turn Sudan into a regional “breadbasket.” In 1977 he launched a six-year plan to bring more than six million feddans (6.2 million acres) into cultivation. This project had two goals: to guarantee Sudan’s food security and to produce animal products and grain for export to the Arab world.

The government expropriated plots from subsistence farmers and pastoralists and doled out vast tracts of land—1.8 million feddans by 1968, four million by 1977—to urban merchants who engaged in a kind of agricultural strip-mining. They cultivated monocrops intensely, gouging quick profits for a few years, while causing increased desertification and a rapid deterioration in soil quality. Overexploitation and uncertain rainfall soon led to poor yields, after which the merchants leased the fields back to the landless for sharecropping. In the process more and more peasants and pastoralists were pushed off their land and forced to seek badly compensated seasonal wage labor. By the mid-1970s, between 1.5 and 2 million people were annually migrating to work on mechanized farms whose yields were collapsing. Some still function today, but they do not remotely meet Sudan’s food needs. Over the past six decades, sorghum yields have declined by half.

The breadbasket strategy failed to achieve its grand aims, but it nonetheless benefited the regime. Nimeiri distributed land leases to chosen elites—part of his creation of a political marketplace based on backroom deals. Corruption intensified in 1977, when his erstwhile enemies, the Muslim Brotherhood, returned to the country as part of a “National Reconciliation” process. They brought along Islamic banks that lent on favorable terms to the cadres of the Brotherhood and to Nimeiry’s regime. In 1982 a Military Economic Board was created, allowing the army to extend its influence into the commercial sector, including in agriculture; this enabled Nimeiri to buy off potential dissidents within the armed forces.

The weakness of Sudan’s food system was cruelly exposed in 1983, when a drought contributed to a 75 percent drop in food production in the provinces of North Kordofan, North Darfur, and the Red Sea Hills. After years of deficient harvests, rural households had little to fall back on, leaving them in no position to deal with the crisis. Scarcity drove prices higher; between 1983 and 1985 the cost of sorghum in Kordofan doubled.

The crisis was exacerbated by Sudan’s high levels of debt. Nimeiri had recklessly borrowed from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the Paris Club—a group of major Western creditors. Much of the money had disappeared into the pockets of his confidantes. In the early 1980s, with Sudan on the edge of default, he accepted a series of IMF-imposed austerity measures as a condition of further loans. These funds—along with continued Gulf investment in “breadbasket” schemes—kept his regime afloat, but living standards were worsening by the day. Subsidies for food and fuel were cut and the cost of basic commodities skyrocketed. By the end of 1983 some 300,000 people had fled northern Darfur in search of food.

Nimeiri tried to conceal the impending famine, which would have announced the failure of the breadbasket strategy, threatening Gulf investment and raising doubts among his creditors, notably the United States, which by then was sending more development aid to Sudan than to anywhere else in sub-Saharan Africa. He hoped that the heavens would save him by bringing good rains the following year. But the drought continued through 1984, with grain production in Kordofan falling to 18 percent of normal yields. Still Nimeiri did not declare a famine and blocked the distribution of food aid. In early 1984 the UN’s Food and Agricultural Organization estimated that Darfur needed 39,000 tons of food. The government, determined to downplay the crisis, made its own assessment and claimed Darfur needed only seven thousand tons. It didn’t appeal for international assistance and only sent 5,400 tons—which was delivered late. Nimeiri was confident that starvation deaths in the rural peripheries wouldn’t bother Sudan’s urban elite.

Then the famine came to the city. By August 1984 some 45,000 farmers had fled their villages in Kordofan in search of food and arrived in the Khartoum metropolitan area. Nimeiri crammed some into trucks and sent them home, but he couldn’t evade the famine’s consequences forever. By 1985 over five million people had been made destitute, a million and a half had fled their homes, and 105,000 had died in Darfur alone.

Resistance to Nimeiri’s regime was already widespread. He had banned trade unions and all political parties other than his Potemkin vehicle, the Sudanese Socialist Union, but professional associations and students led protests against the price increases. They demanded an end to his dictatorship and the creation of a parliamentary democracy. His denial of the famine deepened their outrage. On March 25, a few days before he was to depart to Washington to secure more money, he asked in a speech, “Why do the Sudanese need to eat three meals a day?” His remarks were broadcast and heard by millions of starving people. Students in Khartoum protested, chanting, “The people are hungry! Down with the IMF! The World Bank will not rule Sudan!”

Nimeiri nonetheless left for Washington confident that rioting could be repressed. It was a misjudgment. The students joined with the professional associations and members of the clandestine Communist Party, which called for a general strike on April 6. Other banned parties also prepared themselves for action. After Nimeiri gladhanded with Ronald Reagan, who promised more aid, senior army officers deposed him, and a Transitional Military Council (TMC) took control.

On the eve of Nimeiri’s ouster, civil society groups, trade unions, professional associations, and other political parties formed the National Alliance for National Salvation, which developed a shared agenda: immediate action against the famine, the creation of a parliamentary democracy, and the rollback of the more onerous aspects of Islamic law that Nimeiri had implemented in partnership with the Muslim Brotherhood. This coalition quickly collapsed. While the sectarian parties squabbled among themselves, the TMC exploited differences between the professional groups and the trade unions, sidelining many of their concerns, including their demands for famine relief. After a good harvest in 1985, the TMC announced that the famine was over and ended discussion of reforming the food system. Focused on elections and power in the capital, the political parties dropped the issue. Rural Solidarity—a coalition formed by students and trade unionists active in the uprising—pursued the question of famine in the peripheries for a while, but it was undone by internal divisions and state harassment.

The TMC handed over famine relief to international aid organizations, which were then expanding across Africa, as nation after nation spiraled into debt. Funded by Western donors, these groups stepped in to fulfill tasks, like famine relief, that governments no longer seemed able or willing to perform. In 1985, in partnership with the UN Emergency Office for Sudan, the TMC established a commission to coordinate relief activities. The United States Agency for International Development was made responsible for distributing famine aid; it assigned different international NGOs to different regions of Sudan. (Save the Children got Darfur, Kordofan went to CARE.) Thereafter the internationals were in charge and the Sudanese state was no longer to blame. Famine was depoliticized.

A civil war had broken out on the eve of Sudanese independence between the government in Khartoum and southern rebels. Hundreds of thousands were dead by the time it ended in 1972, with a peace agreement that promised regional autonomy and development projects for the south. As the economic crises of the late 1970s and early 1980s took hold, Nimeiri withdrew from these commitments, leaving a landscape littered with half-built schools and waterpipes leading to nowhere. In 1983 the SPLA was founded in the south with the goal of overthrowing Nimeiri and ending oppressive relations between the center and the periphery. For over two decades it fought successive regimes in the north.

The second civil war (1983–2005) led directly to a series of famines. Perhaps the worst occurred between 1985 and 1988 in Greater Bahr el Ghazal, the heartland of the SPLM/A, where state-aligned Murahiliin militias—drawn from Baggara communities in Kordofan and Darfur—targeted rebel water and food sources. The government only allowed food aid into towns it controlled, a policy echoed by the SAF in the current conflict. This forced people living in rural areas to migrate to urban areas, depriving the rebels of recruits. In response, the SPLM/A laid siege to the towns. The tactics of the two sides immiserated huge swathes of Bahr el Ghazal.

In 1985 Khartoum set up the Humanitarian Aid Commission, which had a mandate to coordinate international aid delivery. The HAC funneled aid to loyalist populations in the north, then repeated the trick in the south. In 1986 62 percent of all aid sent to southern Sudan went to the Equatorian provinces, which constituted only 26 percent of the region’s population, to cultivate them as a counterweight to Bahr el Ghazal. Starvation there forced pastoralists to sell their herds to northern merchants at far below market rates in order to buy food from those same traders, who charged them extortionate prices. Many southerners fled north, where they were robbed by the Murahiliin militias and then crowded into camps in territory held by their tormentors, or else forced to work on commercial agricultural projects in Kordofan.

In 1989 Colonel Omar al-Bashir and the National Islamic Front came to power in another coup, ousting Prime Minister Sadiq al-Mahdi. Bashir faced a volatile political situation: the civil war raged in the south and the economy was creaking under foreign debt. In 1989 a drought in western Sudan, exacerbated by government inaction, led to a famine that spread the next year, when the harvest shortfall in Darfur was estimated at 80 percent. Much of Sudan was affected: by then the economic collapse of the prior decade had increased the number of food-insecure people throughout the country.

Like Nimeiri before him, Bashir did not declare a famine, which would have enabled international supplies to flow to the needy. Instead he intensified state control of humanitarian aid, placing the HAC directly under the national intelligence service, and cracked down on dissent. Limited grain supplies were triaged to politically important constituencies; Khartoum remained the priority. To ensure there was no urban unrest, a newly constituted Food Security Council cut off the water supply to the shantytowns on the capital’s outskirts, demolished the shacks of the displaced, and forcibly removed them from the city. The army diverted humanitarian aid from rural areas to the towns, sometimes at gunpoint. Nimeiri’s ouster, prompted by protests in Khartoum, had taught Bashir a lesson: enormous famines could be withstood as long as the cities were fed.

Bashir’s success eventually proved his undoing. Sudan’s hinterlands grew ever more impoverished, forcing thousands to migrate to the cities, which in turn increased the cost of wheat subsidies. These were paid for by a new form of state revenue: petroleum exports. Oil was discovered in southern Sudan as early as the 1970s, but the civil war had brought exploration to an abrupt end. It began again in earnest only in the 1990s, after Khartoum-backed militias had displaced southern populations living in oil-rich areas. In 2005, following American pressure, a peace agreement brought an end to the civil war; it was followed in 2011 by a referendum on southern independence. When South Sudan voted to secede, Sudan lost access to 75 percent of its oil resources, which constituted the majority of its dollar exports.

Bashir frantically tried to reorient the economy, lending agricultural land to Gulf investors, but it wasn’t enough. The final straw was wheat. In 2018, at the behest of the IMF, his regime cut food and fuel subsidies, tripling food prices and triggering protests around the country. Schoolchildren in Blue Nile who could no longer afford bread took to the streets and chanted against the regime. The uprising soon expanded: in Khartoum migrants from the peripheries marched beside the children of the elite, fed up after thirty years of dictatorship. The protesters demanded a new food system, one that would guarantee food security to all citizens. In April 2019, while this discussion was still in its infancy, Bashir was ousted in another coup, led by a fragile alliance between the SAF and the RSF.

A transitional civilian-military government was established, headed by Abdalla Hamdok, an economist and former UN bureaucrat. Rather than honor the protesters’ demands for a new food system, his government oriented itself toward the IMF and World Bank, which demanded cuts to food and fuel subsidies as a condition for debt relief and more loans, which the state desperately needed to stabilize rampant inflation. The plan failed. In December 2020 inflation was at 269 percent; a year later it had risen to 318 percent. A World Bank–backed Family Support Program, intended to deliver cash to poor families, never got off the ground. Wheat tripled in price. In August 2021 alone, sorghum prices rose by 977 percent. This crisis was felt in Khartoum as much as in Blue Nile.

Both the RSF and the SAF feared that a fully civilian government would rein in their many businesses. (During Bashir’s rule each security service built its own economic empire, with interests in gold, real estate, banking, agriculture, and much else.) Seizing the initiative, the military instigated astroturfed demonstrations in Khartoum against Hamdok’s government and protests in the east of the country. In October 2021 Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, the leader of the SAF, and Hemetti, the leader of the RSF, took power in an autogolpe. Until then the army had held back supplies of wheat flour; now they mysteriously appeared on the shelves of Khartoum’s shops for a few weeks—a repeat of Bashir’s playbook.

The new junta made little effort to address Sudan’s hunger crisis, which deepened when international assistance was suspended following the coup. Then Russia’s invasion of Ukraine almost doubled international wheat prices within a month. By the end of 2022, with Hemetti and Burhan increasingly at loggerheads, the WFP estimated that approximately 15 million people across the country were food-insecure. That year the Sudan Teacher’s Committee conducted a survey of civil-servant wages and found that a teacher’s average income covered only 13 percent of their expenses. High inflation, diminished purchasing power, renewed conflict in Darfur, low food stocks, and erratic rainfall led to soaring food prices and a grain shortfall of 2.75 million tons.

The conflict that broke out in April 2023 is the first civil war to be waged in Sudan’s capital. Khartoum’s residents have fled en masse; its population is estimated to have fallen from six million to one million. Those who can afford it have moved abroad; the rest have escaped to the south, east, and north. At the war’s outset RSF fighters went house to house looting civilian property. Both sides seized humanitarian food stocks. Almost all the international aid workers in the country evacuated, leaving the Sudanese people to fend for themselves.

They have done so admirably. Emergency Response Rooms (ERRs) and grassroots organizations have set up food kitchens, repaired water resources, and practiced mutual aid. They deliver these services in forbidding conditions. Since Khartoum is divided into zones of control, civilian movement is restricted, making it difficult to access markets. Organizers have no choice but to strike deals with the occupying powers. As in previous civil wars, military forces and business elites have profited from hunger. In many parts of Khartoum, the RSF has positioned itself atop an economy of brokers, smugglers, and illicit traders, who are selling essential commodities at prices three times higher than before the war.

From Khartoum the conflict quickly spread west. By the end of November all Darfur’s main cities, except for El Fasher, had fallen to Hemetti’s militia, as the RSF overran the army’s positions and cut its supply lines. SAF’s ground troops, composed of hungry locals, had little incentive to fight for a sclerotic officer corps in Khartoum. In each city, the RSF destroyed state institutions while looting civilian goods and humanitarian resources.

The RSF in Darfur is largely formed of Arab militias, which have used the current war to further a campaign of ethnic cleansing against local non-Arab populations. Just as the Janjaweed did twenty years earlier, the RSF have burned villages, destroyed farmland, and poisoned water walls, displacing or killing Masalit, Fur, and Zaghawa peoples. The Raoul Wallenberg Centre for Human Rights has concluded that these assaults constitute acts of genocide.

In mid-December the war shifted east to the “breadbasket” state of Gezira, which sits to the southeast of Khartoum and is a central zone of Sudanese agricultural production. The RSF rapidly took villages in the north of the state, pillaging markets and homes along the way, before conquering the capital, Wad Medani, with little resistance from the SAF. It has since engaged in industrial-scale looting. The Agricultural Bank was sacked, as was a WFP compound that, according to the UN, contained enough food to feed 1.5 million severely food insecure people for a month. The RSF also ransacked civilian houses and forced farmers to load their crops into waiting vehicles. Many farmers fled. These disruptions contributed to a disastrous harvest.

The war is now entering a new phase. Since the fall of Wad Medani, the SAF has fought back in Gezira and the Khartoum metropolitan area, assisted by Iranian drones and local defense militias. Another part of SAF’s strategy is to spread the conflict, to stretch the RSF thin and pull its forces away from Khartoum and Gezira. One front is El Fasher, held by non-Arab rebel groups who initially stayed ambiguously neutral, striking an uneasy détente with the RSF. In March, however, the alliance fractured when several former rebel factions joined the SAF to attack the RSF in central Sudan. In retaliation the RSF attacked and burned non-Arab villages around El Fasher, where clashes are now taking place inside the city itself.

The RSF has occupied the nearby town of Mellit, cutting off supply routes into El Fasher. Last month militia assaults destroyed parts of the Abu Shouk IDP camp, in the northwest, home to some 100,000 people; the Yale Humanitarian Research Lab reports that the RSF has beaten, tortured, and killed civilians there. Two health centers have already closed; incoming aid trucks meet only 2 percent of the city’s food needs. El Fasher is being starved to death.

The two warring parties are of course primarily to blame for the current catastrophe. But the UN’s decisions have only made matters worse—above all its choice to defer to the SAF for authorization. Legally, UN agencies are beholden to the nation-states in which they operate. In Sudan, though, there is no sovereign state: the SAF lost all constitutional authority upon its coup in 2021, after which the country was suspended from the African Union. In any case, the army barely controls half of Sudan.

What then explains the UN’s deference? It likely originates in Burhan’s decision last December to abruptly terminate its political mission, the United Nations Integrated Transition Assistance Mission in Sudan, which he claimed was interfering in the country’s sovereign affairs. Privately, officials have told us they fear that UN agencies will meet the same fate if they disobey the SAF.

As of June the SAF has allowed only two cross-border WFP aid convoys to come in from Tina, a town in the far east of Chad—the one crossing it controls. It still prevents aid from coming through RSF-held areas of the border, and UN agencies remain beholden to its decisions.

Yet the UN has more leverage than it wants to acknowledge. In meetings we’ve had with humanitarians in regional capitals, the prevailing sentiment is that the World Food Programme is too big to expel, since the SAF relies on it to supply food to territories it controls, which would otherwise be immiserated, threatening support for the army. Some international donors and NGOs have increased pressure on the UN to call the SAF’s bluff. Indeed, several NGOs have been doing cross-border operations since the war began, which suggests the UN can as well.1

Meanwhile the UN’s agencies, based in Port Sudan, are paying the SAF sizable administrative fees and rents. Bureaucratic obfuscation is a lucrative industry. The SAF earns money from its endless permits and often owns the residences in which the humanitarian workers stay and the trucking companies they use for convoys. Many of the agencies’ local staff, internationals have privately told us, also work for the SAF.

The best possible humanitarian plan would be for the UN to move its center of operations from Port Sudan to a regional capital such as Nairobi, outside the SAF’s control. The UN would then establish cross-border hubs in Chad and South Sudan, which would each negotiate directly with local forces, including the RSF. Another purely administrative distribution hub could be located in Port Sudan, for aid going into SAF-controlled territory. The UN might be expelled for cross-border operations. But that remains unlikely, given the needs of those in SAF areas and the dire economic situation in the country more generally.

This is a minimal requirement, not a panacea. The RSF will be as challenging to work with as the SAF. Both belligerents want to divert aid to loyal constituents and block it from reaching their opponents, while coercing payments from humanitarian agencies. They are likely to find some success in these endeavors. But then humanitarianism is always an ethically complicated business.

On June 11 the US special envoy to Sudan, Tom Perriello, told Reuters that “we know we are in famine.” Yet the UN has not yet declared as much. Several humanitarians have told us that the organization is “waiting for the IPC,” which is currently undertaking an assessment, its first since October, in collaboration with the SAF, which has obvious incentives to delay such an announcement. There is no formal reason, however, why the WFP cannot unilaterally declare a famine, which would likely lead to more humanitarian funding and increase pressure on the SAF to grant humanitarians access to RSF-held areas.

Absent a sudden change in policy, Sudan might become the second ruinous UN failure in Africa this decade. In June there was a comprehensive interagency evaluation of the UN-led humanitarian response in northern Ethiopia, the site of a civil war from 2020 to 2023. After years of tension between the Tigray region and the Ethiopian regime of Abiy Ahmed, the war pitted the Tigray People’s Liberation Front against government forces working together with the Eritrean army. Both sides committed massacres; the government put Tigray under siege. Over 500,000 people died, mainly due to hunger and malnutrition-related diseases. The interagency evaluation describes how the UN acquiesced to restrictions on access imposed by Abiy’s government and failed to coordinate its operations coherently. Some 7,700 tons of food aid were diverted to the Ethiopian state and into markets, leading the US, the WFP’s major donor, to pause all financial assistance for five months. The humanitarian response, the evaluation concluded, was a systematic failure. In Sudan, UN agencies beholden to the SAF risk falling into the same trap.

A year into the war, Sudan is increasingly militarized. Facing an acute shortage of infantry, the SAF has armed local communities. For its part, the RSF has expanded dramatically and is struggling to control the forces it has unleashed. Across the country, the war has supercharged ethnic divisions over land and power. In South and West Kordofan, conflict between Arab and non-Arab groups is increasingly disconnected from the battle over Khartoum. Foreign powers are also involved. The SAF has allied with Egypt, Iran, and Russia; the RSF with the United Arab Emirates.

The Biden administration has made a cynical calculation in Sudan. “What you have to understand,” a senior US official told one of us in April, “is that, from the perspective of policy, Sudan is in the Gulf, not in Africa.” In other words, securing a cease-fire in Sudan is less important than keeping the UAE on America’s side: against Iran and with Israel. Thus far the US has not put meaningful pressure on the UAE to cut support to the RSF. It has, however, supported a peace process in Jeddah, in which neither belligerent has shown any interest—effectively as a sop to the Saudi regime.

This war could last for decades, and it is unlikely that the country will be put back together. There is no longer a state to speak of. Sudanese friends talk of a nation of fragments, run by different armed groups. International diplomatic efforts have yet to accept this reality. Instead they dream of a return to the transitional government of 2021, before the coup, with a civilian-led administration amenable to IMF diktats. This is why Hamdok, who has no legitimacy in Sudan, has been serenaded with funds and support by Norway, the UK, and the US. “Forget Khartoum,” an exiled friend told us. “Hamdok cannot even walk through the streets of Cairo without being decried.”

It is easy to forget that hunger in Sudan has a long political history. Droughts might have provoked food insecurity, but governments cause famines. For six painful decades the country’s postcolonial rulers have weaponized hunger, choosing a select few to live and leaving the rest to die. The work of the ERRs and other grassroots organizations suggest another political vision for the food system: one that addresses needs before debts, places people above export markets, and takes as its sovereign principle that no one should go hungry. For such a system to be realized at a national level, at the scale required by the famine, is today unthinkable.