For Kerry James Marshall, art has always been “a set of problems that needed to be solved, the first of which was…the problem of Black representation.” It’s a bit like saying that the first problem to be solved is landing on the moon—a wildly ambitious but not insane goal as long as you are willing and able to tackle the myriad theoretical and technical problems that stand between you and success.

He often tells the story of his kindergarten teacher who rewarded good behavior with the chance to look through her collection of greeting cards, postcards, and clippings. He was dazzled—”partly amazed that they could have been made by somebody, but partly amazed simply because they were there.” Growing up in Birmingham, Alabama, and then Los Angeles, his affections were catholic: Marvel comics, Maxfield Parrish, Botticelli. After seeing a TV ad for decoupage materials, he figured out how to make image transfers from the tipped-in illustrations in library books: “I was probably the only kid in fifth grade in the whole United States who had decals on my notebook [that] were Goya’s Black Paintings.” In 1965, the year he turned ten, a school trip took him to the newly opened Los Angeles County Museum of Art:

I had never been to a museum. I hadn’t known there was such a place…. I went from floor to floor looking at everything, in the same way that in the library I went down the stacks and looked at every art book without discrimination.

But he couldn’t help noticing that in those glorious paintings on the walls and in those tempting color plates in books, “all those figures were white figures. All those angels were white angels. All those nudes were white nudes. All the little cherubs, the putti and stuff…that’s what art looked like.”

The year that LACMA opened, Marshall and his brother watched the Watts riots from their front porch. In 1969 the grounds of his school served as the staging area for an LAPD raid on the Black Panther headquarters, an event that devolved into a shootout involving a dozen party members, more than three hundred police officers, a tank, and some five thousand rounds of ammunition. In its aftermath, The New York Times reported, “a hand-painted sign hung limply above the doorway reading: ‘Free Huey. Feed Hungry Children. Free Breakfast For School Children.’”

The bridge Marshall found between these two worlds was the artist Charles White, whom he first encountered in a book called Great Negroes, Past and Present. In seventh grade, when Marshall was selected for a summer program at Otis Art Institute where White taught, the students were taken to see White’s studio. “There it was…work in progress, and work that was finished,” Marshall recalls. “And so you could see how, in the beginning, how rough things might look. And then you could see how, over time, it became this other thing.” It was proof, he later wrote, that artists “were not wizards, that the work they do can seem magical but in reality is achieved through knowledge, a deep understanding of the principles governing representation, and a willingness to engage in the intensive labor required.”

He planned to enroll at Otis as soon as he completed high school, not realizing it only accepted students with two years of college credits. A dishwashing job was followed by a factory job making asbestos floor tiles. Laid off in the recession of 1975, he registered at Los Angeles City College, arranging his class schedule around visits to the unemployment office. He took classes in children’s literature and storytelling, hoping to become a book illustrator on the model of early twentieth-century greats such as N. C. Wyeth, Howard Pyle, and Arthur Rackham. “As far as I understood,” he told me, “nobody ever expected to make a living out of selling paintings through a gallery.” A mandatory course in public speaking asked students to demonstrate a skill for the class, and Marshall chose woodcut, though he had never made one before. The result was Brother (1976), a roughly silhouetted head of a Black man with a jutting beard, much indebted to a Charles White etching from the previous year. But where White’s print is large and nuanced, Brother is small and austere, cut into a piece of salvaged two-by-four lumber so narrow the head is slightly flattened at the back where Marshall ran out of room.

When he finally arrived at Otis in 1977, White was still there—“the gift that kept on giving”—but the curriculum had moved away from the old skill set of drawing, color theory, and composition in favor of more conceptual approaches. “There I was,” he told the curator Dieter Roelstraete in 2014, “wanting to learn all these techniques, wanting to master the art of constructing pictures, and the first thing I hear is that I no longer need to know all those things because nobody is doing that kind of stuff anymore!”

The problem was personal (he liked figurative pictures and aspired to make them) and also political (how could you amend the whiteness of the figurative canon without being competent in figuration?). Instead of going on to graduate school, he immersed himself in the LA art world. With an eye on the example of Romare Bearden, he worked in collage, and the experience of assembling scraps of color magazine pages attuned him to the astonishing chromatic diversity of printed blacks—red blacks, green blacks, warm blacks, cool blacks. Separated, those differences escape notice, but adjacent to one another, they produce optical depth as well as a salutary conceptual adjustment to what we mean by “black.”

Around this time Marshall read Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man, with its famous description of Black erasure: “I am a man of substance, of flesh and bone, fiber and liquids—and I might even be said to possess a mind. I am invisible, understand, simply because people refuse to see me.” Marshall is skeptical of claims that visual art has the power to mobilize viewers politically. What it does have, he observes, “is the capacity to direct people’s attention toward things.”

The picture Marshall considers to be his breakthrough work, the first in which he successfully deployed “blackness as a rhetorical device,” is a painting on paper no larger than a standard paperback, executed in egg tempera using Cennino Cennini’s fifteenth-century treatise as a guide. Portrait of the Artist as a Shadow of His Former Self (1980) shows the head and shoulders of a Black man in a black jacket and black hat against a near-black background. A triangle of white shirt, two eyes, and a spread of gleaming teeth (one missing) disrupt the darkness, but the darkness itself is complicated, existing in different tonalities and depths.

There is more than a hint of minstrel-show mockery about Portrait, amid a wide assortment of cultural references. The title and fedora are borrowed from James Joyce, the invisibility from Ellison, and the visual devices from Quattrocento figuration and Ad Reinhardt’s black-on-black abstractions. The image nods to the old saw about Black people being invisible at night unless smiling or wide-eyed, but the wild grin was taken from the 1961 B-movie Mr. Sardonicus, whose European title character digs up his father’s body to retrieve a winning lottery ticket and is so traumatized by the sight of the skull that his own features freeze in a ghoulish rictus. Portrait’s peculiar combination of brazenness and optical nuance does many interesting things, but first of all it makes you look.

It is also a curiously printerly painting—small and executed on paper in a medium that encourages hard edges and flat colors. (Egg tempera’s quick drying time precludes the soft gradients, sfumato, and translucency of oil paint.) Tones were produced by crosshatching rather than blending, and it is not difficult to see a genealogical connection to Brother.

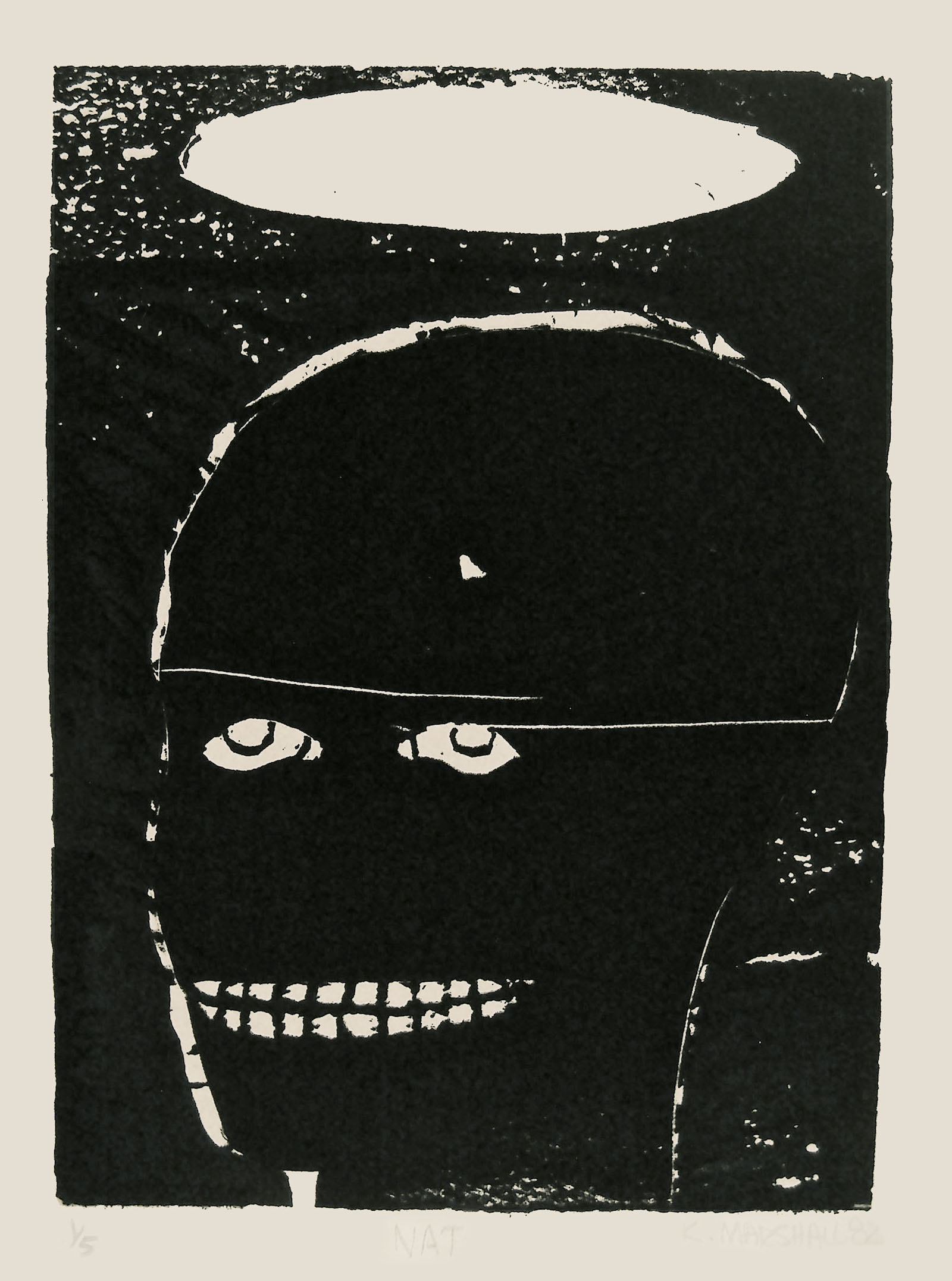

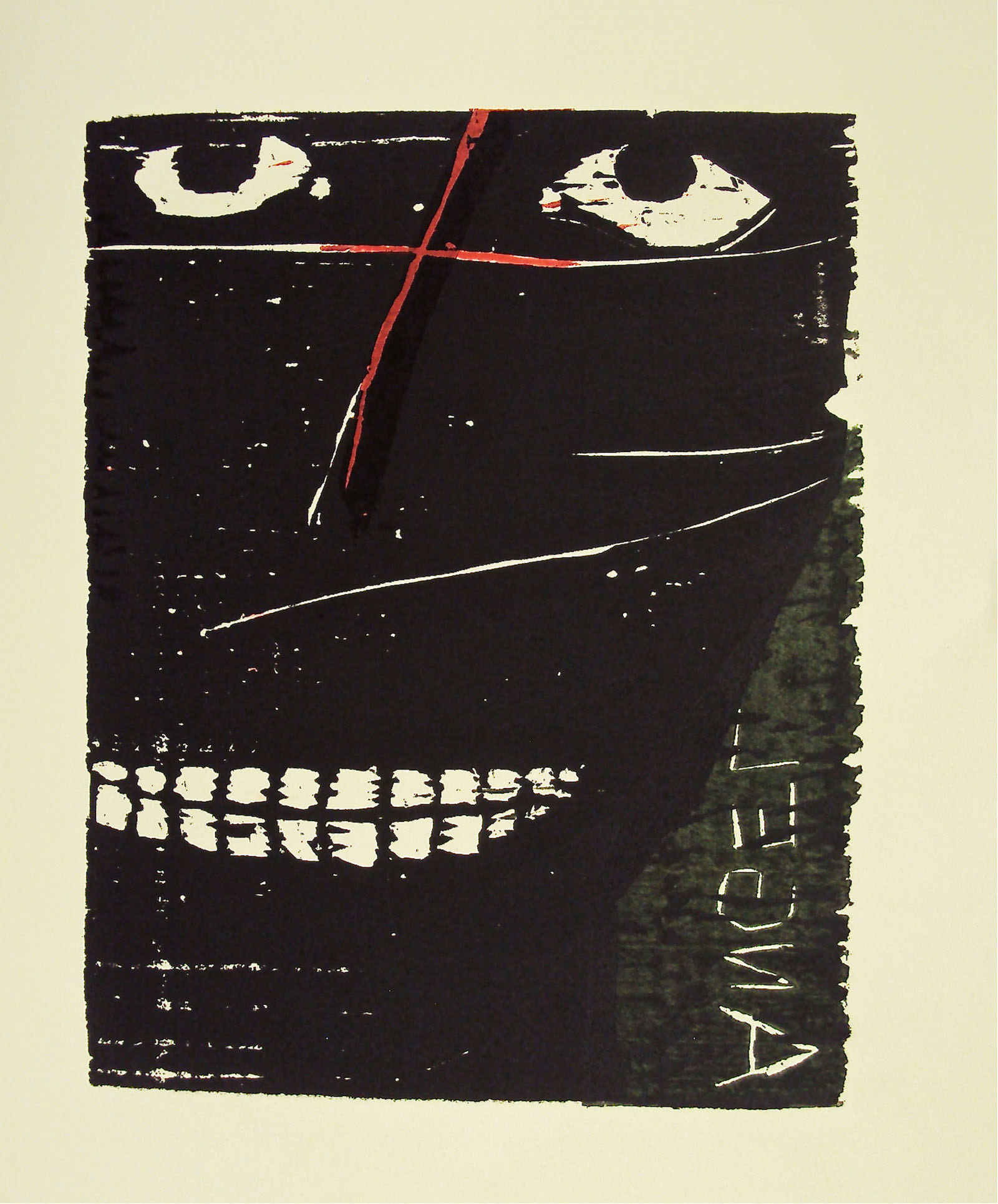

Still print-curious, Marshall acquired a small tabletop “show card” press, originally sold to shop owners to make in-house notices (“Winter Gloves Half Price!”), but also, he realized, useful for printing small linocuts and woodcuts. It became a field of play, free from the niceties of numbered editions or, for that matter, the expectations of “serious” art: “I simply made stuff to see what it was going to look like.” The results could be waggish—as in his color linocut of a personified crank telephone lying in bed, lonely and aroused—or stealthily profound. A seven-inch-tall homage to Nat Turner echoes the gleaming teeth and eyes, the near-miss black hues of Portrait of the Artist, as well as its quattrocento connections—in this case, a flying-saucer nimbus.

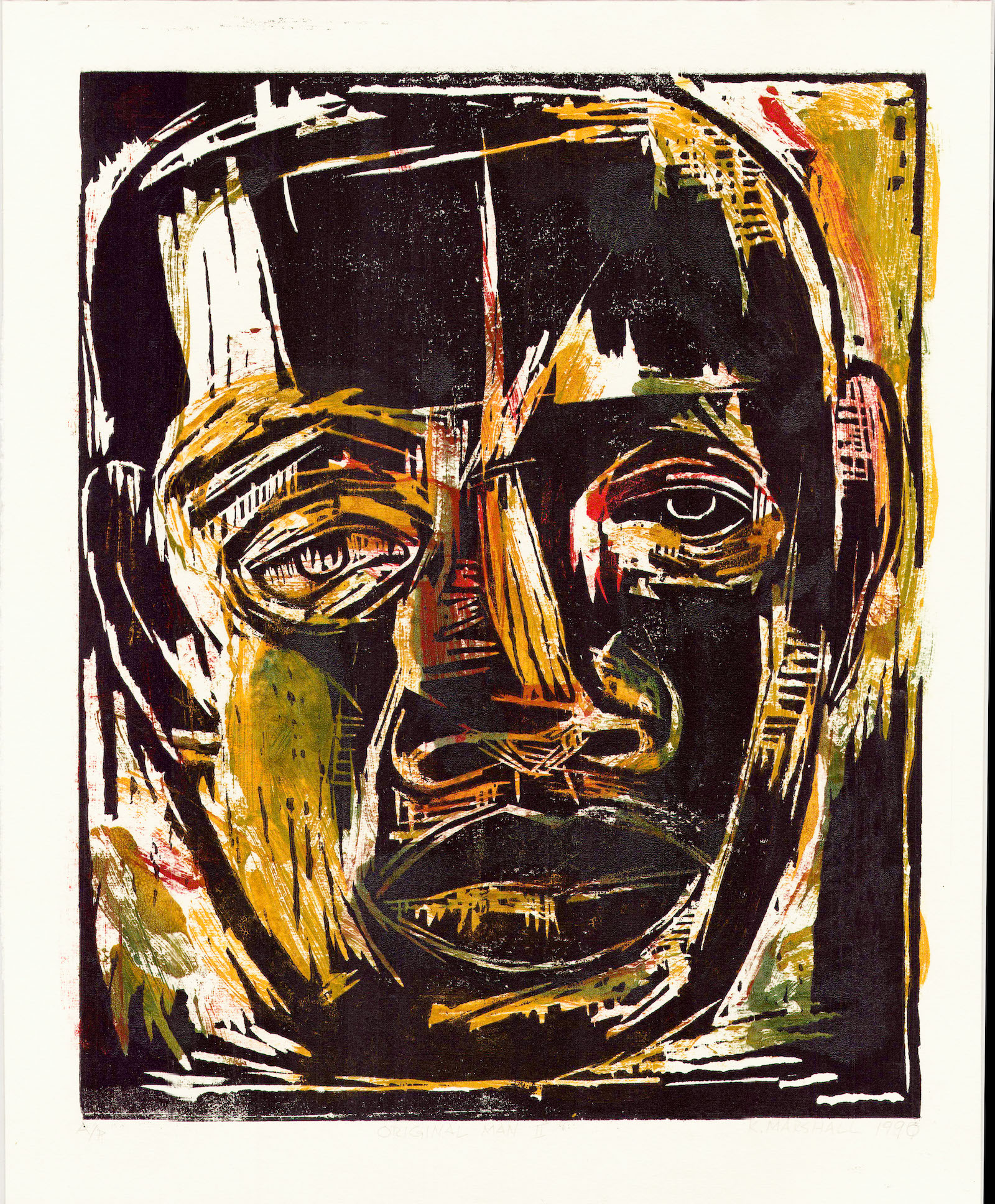

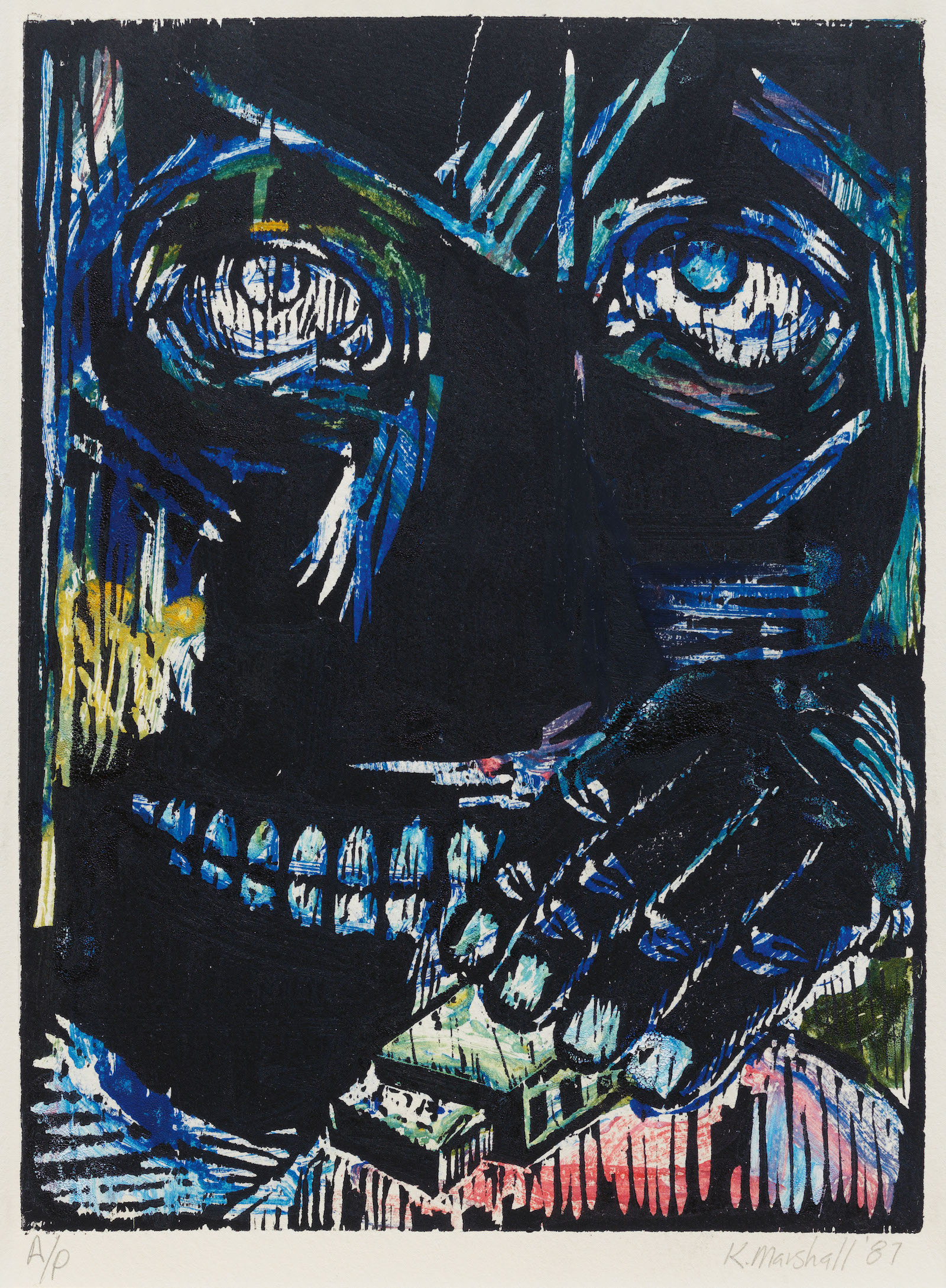

For printing blocks he used “random planks of wood” found in the street, preferring the not-blank slate. Chipped, scratched, aberrantly trapezoidal, each block was a call awaiting a response. Marshall, a passionate fan of the blues and an avid harmonica player, was seeking an artistic method that would summon that magical combination of rawness and virtuosity. Using his little press, he joined two unpredictable processes—the ornery scrap-lumber woodcut and the slippery medium of monotype—together. First he applied oil paint to smooth plexiglass to print one-off, colorful, inchoate compositions; then he would design a woodcut to print over each one. It is common in printmaking to start with black-and-white design and then add color, but Marshall reversed the order of operations, and since the oil paints would never land the same way twice, guaranteed that he could never repeat himself.

His two extended series of monotype/woodcuts are at once rougher and more jewel-like than anything he has done before or since. One series focused on the heads and hands of musicians (almost all are playing harmonica and are, as he acknowledges, at some level stand-ins for the artist). A second series explored orishas of the Yoruba pantheon, each small block filled with jagged slashes revealing turbulent color beneath a black head and sardonic grin.

Until the 1990s most of Marshall’s compositions asked to be read as images arrayed on a flat surface rather than stepped into as a world. That changed with The Lost Boys and De Style (both 1993), multifigure paintings that retained a collage sensibility within a spatially coherent universe. The new paintings did three critical things: they drew viewers in by speaking the language of the Western pictorial canon fluently; they committed generous space to Black figures; and they placed them in a contemporary Black world that was at once mythic and ordinary. Their large size (De Style is almost ten feet wide) was practical (these are compositions with a lot going on in them) as well as tactical. Scale is one way to lay claim to authority.

The power of prints has historically lain elsewhere—in their ability to insinuate themselves into daily life, foster private one-on-one experiences, or be seen in many different places at the same time. Only once has Marshall made a print designed to commandeer space in the fashion of grand manner painting. Untitled (1998) is an eight-color, twelve-panel woodcut running more than forty-eight feet in length and depicting a sociable gathering of young men.

Unusually for an artist of his stature—he had been named a MacArthur fellow two years before making Untitled—Marshall dislikes delegating even the grunt work of art production. He has no studio assistant and does not rely on professional master printers when he can possibly help it. For Untitled he cut thirty full-size sheets of plywood (some more than once, after builders mistakenly took them for scrap). To print them, he bought a linoleum floor roller and added free weights to the axle.

Walking from left to right, the viewer passes from the outside of a brick high-rise, through a window with a blooming flower box, into a living room where six young men chat in small groups, seated on the sofa or cross-legged on the floor. Empty plates suggest the end of a convivial meal, and the host is seen with a coffee pot on the threshold of the kitchen. The scene continues down a hallway and past a doorway opening onto a tidy bedroom. The subjects’ graceful leisure echoes the fête champêtre (garden party) tradition pursued by painters from Giorgione to Manet, but Marshall replaced the familiar single-point perspective—everything arranged for the benefit of a viewer standing in a fixed position—with a panorama, and relocated the action from the usual verdant garden to an apartment whose high floor, economy-line window, and mid-century brickwork announce public housing.

The specific site he had in mind was the Robert Taylor Homes, a Chicago public housing project that was named the second-poorest neighborhood in the country in 1995. The poorest neighborhood was Stateway Gardens, next door. Both were just down the street from the abandoned (though recently squatted) house Marshall and his wife, the actress Cheryl Lynn Bruce, had bought in the South Side neighborhood of Bronzeville.

Once known as the Black Metropolis, Bronzeville had been a popular terminus for the Great Migration in the early twentieth century, a vibrant center of Black music, literature, social action, and entrepreneurship. Photos show thoroughfares alive with stores, restaurants, and clubs, as well as leafy boulevards lined with impressive homes sprouting towers, balconies, and wraparound porches. The Mies van der Rohe–designed campus of the Illinois Institute of Technology, a bastion of modernist design, was built in Bronzeville.

IIT was still there in 1992, when Marshall and Bruce moved in, but most of the grand houses were derelict and surrounded by empty lots where others had burned to the ground. The lively storefronts had given way to busy street crime. Gunfire was commonplace. When the kitchen windows in Marshall and Bruce’s house were shot out one New Year’s Eve, the only advice the police had to offer was to stay away from the windows.

At the same time, of course, Bronzeville was a neighborhood of regular people trying to get by. On the block where Marshall still has his studio, students walked to school and streetwalkers plied their trade. A white van would pull up and park in the same spot every day, its occupants talking and listening to music for hours on end. Rothschild Liquors and the Crusaders Ministries both found their clientele. Next to the Chicago Rib House a turn-of-the-century townhouse bore a sign announcing the “Ancient Egyptian Museum” created by an Afrocentric writer named Walter Williams, who hoped his collection of reproduction artifacts and contemporary paintings might bring “forth the resurrection of the ancient Egyptians into the spiritual and mental consciousness of those who call themselves blacks or African-Americans.” All in one city block.

Around the time that Marshall was carving his monumental idyll of young Black men at urban leisure, the city of Chicago decided to demolish tens of thousands of units of public housing, including the Robert Taylor Homes and Stateway Gardens, in a bid to quash gang violence. It did not really work, as the city’s subsequent history has shown, but in the resulting dislocation (tens of thousands of people were forced to move) and the existential cultural dynamics of such disruption, Marshall saw the seeds of an epic saga of loss, love, and competing notions of redemption.

Invited to develop a new work for the 1999–2000 Carnegie International, Marshall devised “a conceptual work about black absence in daily newspaper comics,” a game of looking and overlooking. In an apse in the Carnegie Museum normally dedicated to bijou decorative arts, he placed small origami sculptures inside glass-fronted cases—boat, hat, cup, dustpan, balloon, airplane, and a not-strictly-origami palm tree that required some scissors-work. He then lined the display-case glass with newspaper comics in the manner of a shop undergoing refurbishment, such that the paper treasures could only be glimpsed through cracks between the haphazardly arranged newsprint sheets.

Visitors who took the time would notice that all the obstructing newsprint came from the same color comics—all written and drawn by Marshall. With patience, it was possible to identify bits and pieces of a story set in a futuristic place called the Black Metropolis. The story hinted at in the Carnegie comics revolves around a young prodigy named Stasha, studying robotics at a school much like IIT, and her boyfriend Farell, who lives in a soon-to-be-demolished project much like Stateway Gardens. When Stasha is paralyzed in a shooting, she uses her technological genius to regain mobility and exact revenge, directing driverless cars to carry out drive-by shootings of gangbangers. Farell, meanwhile, stumbles into the “Ancient Egyptian Museum” down the block from Marshall’s studio. There the shaman-like Rythm Mastr teaches him drumming patterns that can awaken the supernatural powers latent in African sculptures, which Marshall shows on display in a museum looking much like the Art Institute of Chicago.

Marshall selected “a very specific set of African sculptures that had certain attributes that could easily be translated into superhero powers”: a faceless Senufo Kafigeledjo (he-who-speaks-the-truth) oracle; a nail-studded Nkisi Nkondi who can pull speeding bullets to himself like a magnet; the blobby quadruped Boli, a kind of spiritual battery that can wreak havoc on a roadway; Oba, a warrior king with the power to fly; and the twin Ibeji, endowed by Marshall with the power of splitting into two when attacked, so as to multiply in the face of adversity.

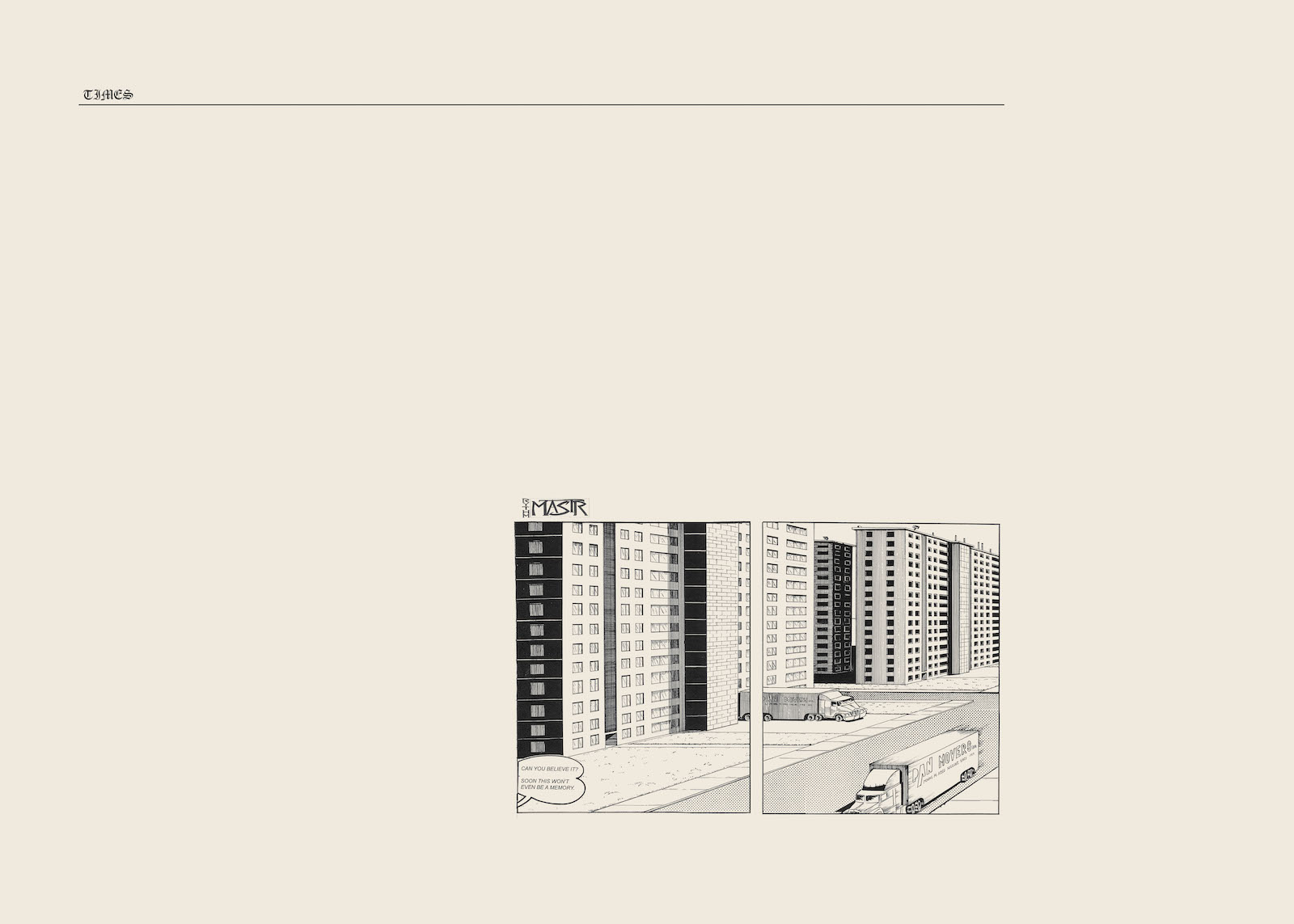

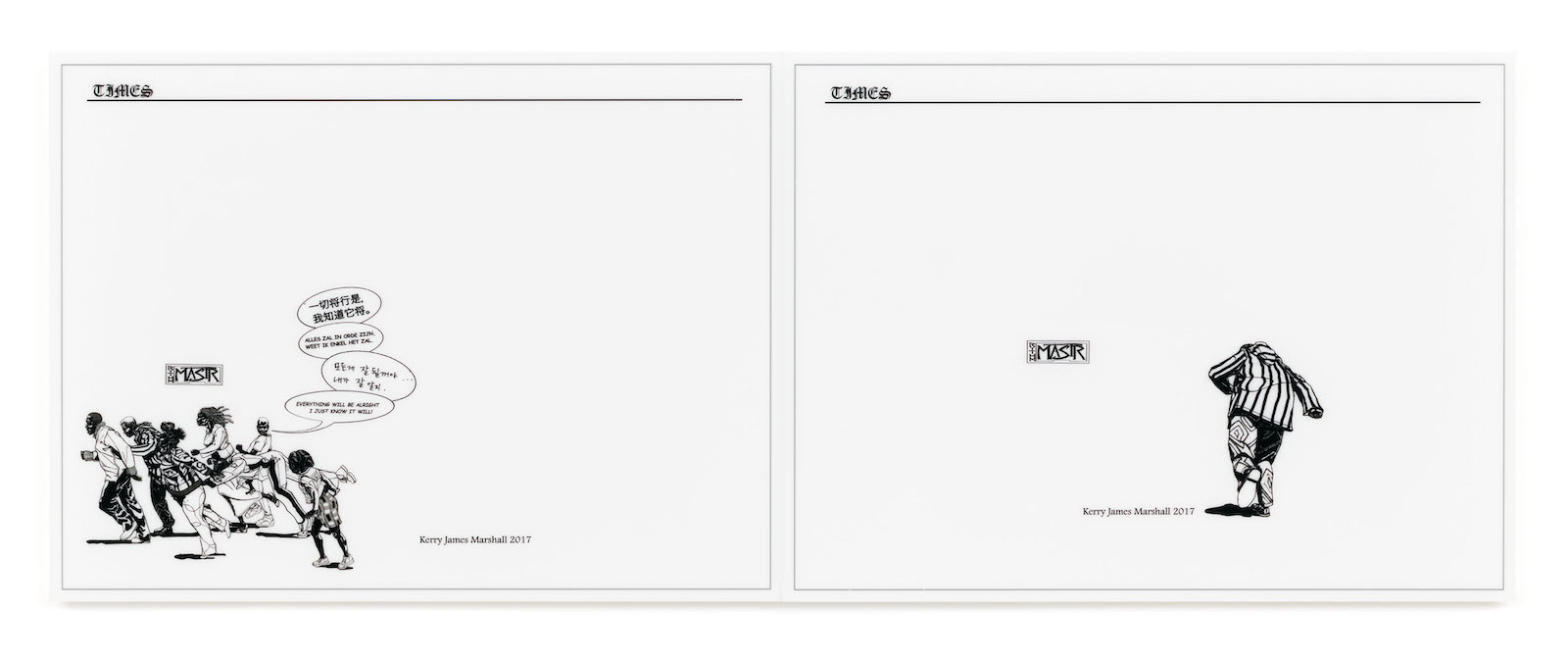

The Rythm Mastr Dailies Marshall began producing in 2003 are large sheets topped with a newspaper-like header and rule, each bearing one or two short cartoon strips afloat in empty space. The Rythm Mastr story of Stasha, Farell, and the African superpowers was joined by new strips. There is P-Van, which relays the conversations and arguments taking place inside a white van, much like the one that parked so often by Marshall’s studio (“Fuck the founding fathers! They were racist, fuckin profiteers to a one!” says one bubble; “Not John Adams,” objects another). The women of Ho’s Stroll roam the pages at will, unfettered by frames. Later, the On the Stroll strip will give them space to chat about work and debate the merits of Afrocentrism and postmodernism in Black American English. Marshall is equally attuned to art-world vernacular: P-Van is sometimes subtitled “a discursive vehicle.”

Reflective, rude, poignant, and hilarious, these threads spin out in different directions, occasionally crossing paths to let you know that they are all part of the same story. “The inconsistency is as much a part of the artworks as anything else,” he explained as we looked through the series. “So if there are threads that just kind of drop off, or a gap that doesn’t get picked up someplace else, that’s just a part of the way the presentation is operating.” They touch on public policy, the relative claims of the present and the past, the limits of technology, and on mechanisms of cultural adaptation and survival.

Though Marshall almost never repeats the same strip, one phrase has emerged as a kind of Rythm Mastr refrain, spoken by various characters in different situations: “Everything will be alright… I just know it will!” It struck him as quintessential comics-speak—slightly leaden yet somehow captivating in its earnestness, at once lame and heartening. Often it is spoken by a young woman to a distraught young man, but the choreography changes, the gender roles can vary, the voice bubble may emerge from a crowd or from outside the frame.

Drawn with extraordinary precision in India ink (“they take forever,” he says), the drawings track Bronzeville streets as assiduously as the vedute of Canaletto replicated eighteenth-century Venice and London. To ensure continuity as the pictorial action moves through space, Marshall constructs sets out of cardboard boxes, plastic food containers, Lego bricks, and other supplies, modeling the human actors with poseable figurines—Barbies, McFarlane basketball players, superhero dolls. (His favorite is a Jessica Alba action figure from the Fantastic Four franchise, sporting twenty-eight points of articulation.) For their costumes he bought a Singer sewing machine, learned to sew, and with the help of Aya-Nikole Cook (the only assistant he has ever had in the studio) amassed a wardrobe of doll-sized garments made from socks, ties, underwear, napkins, and placemats. The vaguely futuristic blockiness of Rythm Mastr fashion is at least partly the result of the collision of scales: buttons are strangely large and fabrics unexpectedly thick relative to the diameter of an arm or neck.

The ultimate realization of Rythm Mastr, Marshall anticipates, will be as a film, and he employs lots of cinematic devices—establishing shots, long pans, and arc shots that rotate around a subject. In his Everything Will Be Alright triptych, even the speech bubbles spin. To suggest the optics of movies, he tried using lightboxes but abandoned them as too bulky and technically unreliable, and turned instead to a technology most often used for commercial signage, UV-printing. Inks cured with ultraviolet light can be printed digitally on a wide range of surfaces, producing a weather-resistant image with fine lines, flat tones, and no need for framing or protective glass. Applied to a translucent, milky-white plexiglass as the substrate, Marshall’s drawings take on a luminosity somewhere between frontlit paper and backlit screen.

These new options gave rise to a new Dailies format in which strips are abutted end-to-end in a physically continuous but narratively interrupted line. The ten sections of Rythm Mastr Daily Strip (Runners) (2018) are just seven and a half inches tall, but cumulatively they run almost sixty feet, carrying a story that, like a movie teaser, is peppered with jump cuts and elusive connections between events—an art opening, a comedy club, people fleeing on foot, speeding police cars, and an Oba figure flying through the sky. Rythm Mastr Daily Strip (Drum Solo) (2021) breaks the pattern by concentrating on a single event—a drum solo at Jim Bey’s nightclub in the Black Metropolis—because, Marshall observes, “nobody ever pays attention to a drum solo.”

Sitting in his studio amid Rythm Mastr maquettes, his old table-top press under a pile of books, duffle bags full of woodcut blocks, and mock-ups for his stained-glass windows then being installed at the National Cathedral in Washington DC, Marshall reflected:

I don’t like things that don’t take a lot of time to develop. I like building. One of my favorite quotes from one artist about another was Duchamp talking about Seurat. He said he liked Seurat a lot because Seurat “made his big paintings like a carpenter.” I like that. That’s my approach—like a carpenter.