Last year, on holiday in Cornwall, I found a copy of A Private View of Stanley Spencer in a secondhand bookshop. I was only a few miles from St. Ives, the fishing village where the eccentric English painter—whose work inspired, among others, Lucian Freud—and his second wife, Patricia Preece, spent their six-week honeymoon in the summer of 1937. The book is Preece’s memoir of their highly unconventional and often fraught relationship, ghostwritten by the novelist and biographer Louise Collis in the spring of 1962, three years after Spencer’s death. Collis wrote under Preece’s close direction, in the first person, because, as she explains in the introduction she later added to the text, “it was originally intended that the book should be published under her name alone.”

In her introduction, Collis admits that before meeting Preece she’d heard enough gossip to put her on her guard: that Preece had ensorceled Spencer, thus wrecking his marriage to his first wife, Hilda Carline; rapaciously spent his money; then refused him his marital rights, declining, throughout their marriage, to live with him. In short, she’d made his life a misery. But the woman Collis met was “charming,” kind, and eager to talk. The two of them quickly established a rapport. In 1972, six years after Preece died, the book they’d worked on together—now described by Collis as her “memorial to a strange friend”—was finally published.

Flicking through its pages, my eye caught one of the photographs: Preece and Spencer on their wedding day, outside the registrar’s office in the Berkshire town of Maidenhead, near the village of Cookham where they lived (separately). Spencer stands stiffly in the middle of the frame—a rather creepy, goblin-like man, notably shorter than both his bride, who’s on his right, and his best man, on his left. He wears an unbecoming, floppy-brimmed canvas hat, and his thick-framed, bottle-bottomed spectacles magnify his eyes. Preece’s face is half-hidden by her own large hat; she looks not at the camera but off to the right. It’s an awkward tableau, without a trace of intimacy.

It wasn’t until last month, at an exhibition at Charleston’s new gallery in Lewes, that I realized a fourth figure had been cropped out of the picture in the book: Dorothy Hepworth, described in A Private View as Preece’s “lifelong friend.” Her hair neatly Eton-cropped, wearing a buttoned-up cardigan, blouse, tie, and long skirt, she grasps a large leather handbag defensively in front of her. In the original image, the four figures are neatly split down the middle. Two couples: Spencer and his best man, Jas Wood, on the right; Preece and Hepworth on the left. The two women are standing close, Preece’s body leaning slightly into Hepworth’s, their arms touching. They’re the real couple here.

It was in fact Preece and Hepworth, not Preece and Spencer, who spent the subsequent wedding night together and boarded the train for St. Ives the following morning. (Spencer, meanwhile, remained in Cookham to finish a painting he was working on, during which time he slept with his first wife.) Not that they were giddy newlyweds. By the time the photo was taken, the two women had been romantically involved for nineteen years.

They met in 1918, when Hepworth was twenty-three and Preece was twenty-four, as students at London’s Slade School of Fine Art. Hepworth grew up in a prosperous household in the Midlands city of Leicester. Her father was a prominent knitwear manufacturer, and her mother had her own money from her family’s sheep-farming business. They were modern-minded, supportive of both Hepworth’s ambitions and those of her younger sister, Marjorie, who studied science at Somerville College, Oxford.

Preece’s background was less affluent, though hardly impoverished. She was born in the London borough of Kensington and christened Ruby Vivien; her father was an army officer. Her early life was significantly more eventful than Hepworth’s. At eighteen she changed her named to Patricia, as Denys J. Wilcox writes in his new book The Secret Art of Dorothy Hepworth aka Patricia Preece, “after a scandal the previous year surrounding the death of W. S. Gilbert (of Gilbert and Sullivan fame), when she had been swimming in his lake and Gilbert died from a heart attack whilst attempting to rescue her from drowning.” The coroner declared it an accidental death, but a certain notoriety persisted. She also participed in the women’s suffrage movement, and was briefly engaged to a naval officer.

Preece arrived at the Slade in the summer of 1918. She and Hepworth had an immediate connection, and soon they were inseparable, surreptitiously spending their weekend nights together in Hepworth’s college room. When they left the Slade in 1921—Hepworth graduated with First Class honors—they set up in a studio, which came with a small apartment, on nearby Gower Street. It was paid for by Hepworth’s father, as was common at the time for families of her class and means. What was less conventional was that they lived there as a couple, sharing a bed, as they would do for the next forty-five years.

These were not accepting times. Lesbianism wasn’t criminalized, like male homosexuality was, but it was hardly tolerated. So polluting was it thought to be, Wilcox reminds us, that in 1928 the editor of the Sunday Express declared that he would “rather give a healthy boy or a healthy girl a phial of prussic acid” than allow them to read Radclyffe Hall’s new sapphic novel The Well of Loneliness. At the same time, many young working women in London cohabited as flatmates, especially in the aftermath of World War I, when a generation of marriageable females lost their potential partners and had to look for other models of financial security and domestic companionship. The increased ubiquity of these platonic shared living arrangements likely made things easier for couples like Hepworth and Preece, anointing their domestic setup with a degree of legitimacy.

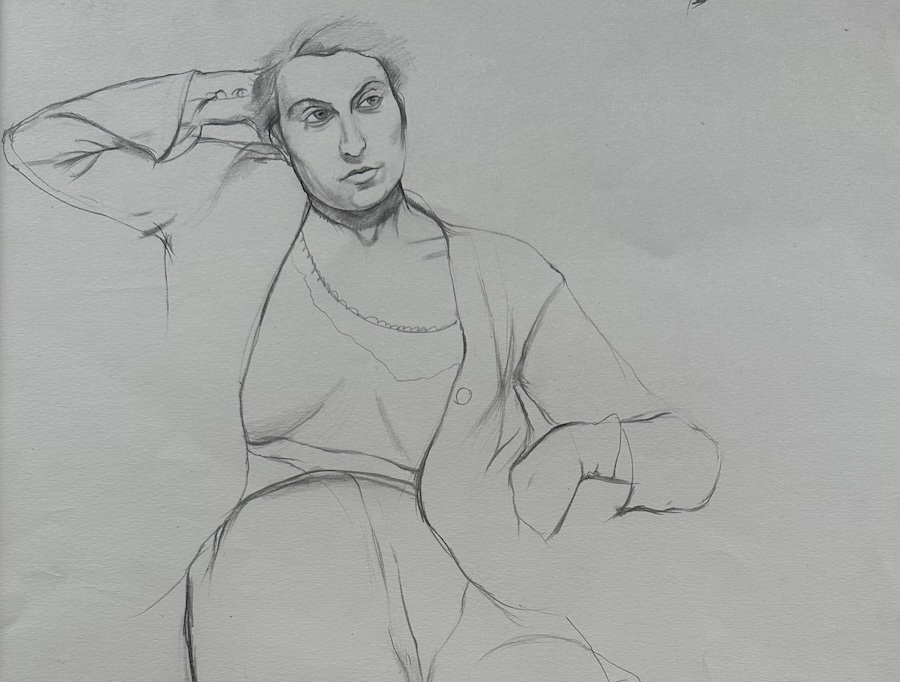

The exhibit at Charleston, “Dorothy Hepworth and Patricia Preece: An Untold Story,” includes a collection of Hepworth’s pencil sketches from these years. Sometimes, as in Woman in Profile and Seated Girl (both circa 1920), the model is unidentified, but Preece is the figure who dominates. Hepworth draws her lover over and over again, fully clothed and naked. There’s a sketch of Hepworth’s mother from the same period, the older woman seated on a wooden chair, her hands clasped together in her lap, her face in stern but calm repose. Hepworth’s pencil lines are firm and clear; the bodies of her models are substantial, shapely beneath their clothes, but it’s the faces that command attention, a rich sense of character achieved in a few lines.

That there are no works by Preece from this period isn’t strange. Shortly after moving in together, the lovers embarked on an artistic collaboration. As the more charismatic of the two—very much a New Woman—Preece cannily sought out the support of Roger Fry, London’s preeminent art critic and a central member of the Bloomsbury Group. Leaving her shier partner in their studio, Preece took examples of both their work to Fry’s home. Unimpressed by Preece’s paintings, Fry immediately recognized Hepworth’s talent, but rather than admitting which work belonged to whom, Preece let Fry believe that she was responsible for the superior canvasses.

It was the start of an elaborate deception. Henceforth Hepworth signed all of her work with her lover’s name, then Preece took it out into the world to sell as her own. Fry, Virginia Woolf, Vanessa and Clive Bell, Duncan Grant, Augustus John, and Gwen Raverat were just a few of the artists and critics who publicly championed and supported Hepworth’s painting for years, all while believing that Preece was the artist.

The truth wasn’t widely made public until after both their deaths—Preece died in 1966, Hepworth in 1978—when, in the 1990s, the curator and collector Michael Dickens organized a series of posthumous exhibitions that properly attributed the art. But “An Untold Story” is the first show to offer a comprehensive account of Hepworth and Preece’s life together alongside the work. Charleston is a fitting venue: primarily Vanessa Bell’s home, it also served as both studio and canvas for the Bloomsbury Group, which Preece and Hepworth eventually joined, thanks to Fry’s patronage, as, in Preece’s words, “junior members.” It was a great honor, even if they found the gatherings “rather solemn” and reeking of “the exclusive club atmosphere.”

The paintings themselves make up a revealingly intimate collection, a panorama of quiet, domestic village life. Many feature the interior of Hepworth and Preece’s cottage: small, dark rooms, full of furniture, with low, sloping ceilings; snapshots of the women’s private life together. Hepworth’s early still lifes, some painted during the four years in the early 1920s when the couple lived in Paris—Fry had suggested they decamp there—echo Cezanne’s: burnished oranges or rosy apples among wine bottles and polished earthenware cassoulet pots. There’s a stunning early oil (circa 1920) of Preece perched on stones on a beach in Cornwall that’s more impressionistic than Hepworth’s later portraits of her lover: the vivid pink of Preece’s dress clashes delightfully with the rich, mustardy tones of the landscape.

The show includes many of Hepworth’s later nudes, painted in the mid-1930s, which have a soft, sultry voluptuousness: in After the Bath and Model with Red Hair (both circa 1937) the sitters are perched on chairs, unadorned but for towels draped over their legs. The dark backdrop of each painting accentuates the gleaming brightness of bare flesh. The creamy rose-tinted hue of the skin of the woman in After the Bath glows gently, while the alabaster coolness of the red-haired woman emits a fluoresence that mirrors the light reflecting off of the large white porcelain jug and bowl on the washstand beside her. Drawings of her nude lover from a decade earlier, meanwhile, although manifestly erotic—Preece’s legs spread wide—are tender and loving too, especially when compared to what Preece herself described as the “twisted sensuality and…amazing ugliness” of Spencer’s later portraits of her.

Some of the most prominent canvases in the exhibition are portraits that Hepworth painted of various neighbors. Their domestic, Louie Farrell, was a favorite model. Hepworth painted her as she would anyone else, seated properly rather than going about her daily duties: in a diary entry from the late 1920s Preece called her “useless as a daily” but “the most paintable model we’ve had since Paris.” Another regular was the village’s elderly baker, the delightfully named Ben Buttery, who’d honed his skills as a sitter modeling for Spencer. With a bottle of beer at hand, such as the one at his side in Ben Buttery and Beer Bottle (circa 1932), he was content to sit for hours. These paintings are informal and warm, their setting resolutely homely.

One could argue that this was the only mise-en-scène safely available to Hepworth, but her dealings with Farrell suggest that she was significantly less interested in the stature of her sitters than in the complexities of their faces. Portraiture was clearly her métier, as the bulk of the exhibition attests, but unlike most other portraitists of talent, she was unable to take on more prestigious commissions. In 1935, in an attempt to help Preece earn some much-needed money, Bell asked her, on behalf of her sister Woolf, to draw a portrait of the composer Dame Ethel Smyth. Bell even offered Preece her own London studio, as the elderly sitter wouldn’t schlep out to Cookham. “I think if you’d do the portrait of a well-known person like that it might possibly lead to other orders, and it would certainly be seen by lots of people,” she wrote benevolently, using an argument that was hard to rebut. Alas, Preece had to turn it down; “she could not reasonably have taken Dorothy along to make the drawing,” Wilcox writes, “without exposing their secret.” Both Bell and Woolf assumed that the artist was too shy.

As Kenneth Pople argues in Stanley Spencer: A Biography (1991), Hepworth “simply wanted to be allowed to devote her whole life to painting.” That was lucky since the couple needed the money: after Hepworth’s father died in the early 1930s, it was revealed that the family had nothing left. Pople and Wilcox both note that Hepworth took on the traditionally “male” role of artist and provider, while Preece acted as helpmeet. But in other ways their relationship subverted those dynamics. In 1932, frustrated by their worsening finances, Preece recounted in her diary how “disagreeable” her partner had become. Wilcox relates that Hepworth responded in pencil the following day—itself evidence of the intimacy between them—invoking her sister, with whom she had a strained relationship:

Each day sees my life nearer ruin, and my painting I have resigned to make nothing. I can’t help respecting those who can push and get something. I wish to God someone like Marjorie would do it for me so that I could continue to paint. I can’t help respecting it and wish I lived with Marjorie. Not Marjorie, I hate her character, but if saying to me you care for my painting, you ought not to see it as just an end and what it will do. That is why I say we are inefficient and hopeless. In this view, you can’t think of anything that would help me and my painting, and I’ve always depended on you thinking of things, I can’t help it, I’m no good myself. I sneer at you I think because you can’t help me to get any help or anything…and I see myself wasted, I suppose I am terribly egotistic.

But if she was in some respects an art monster, her utter disinterest in public recognition was also oddly non-egocentric. Similarly, at first glance Preece seems like the more domineering partner, but on scratching the surface one discovers her devotion to keeping Hepworth happy and honoring her talent. Early in the exhibition a striking display of small black-and-white photographs in a four-by-six grid shows Hepworth posing by twenty-four of her paintings, a private record of her oeuvre archived by her proud partner. From the snap decision Preece made during that first visit to Fry’s house through the writing of A Private View, which contains not the faintest hint of what she and Hepworth really meant to each other, Preece—clearly a talented artist of a different kind—took every opportunity to deflect public attention away from Hepworth. In his biography of Spencer, Pople observes that the two women “presumably…agreed between them that continuing the subterfuge was the best way to consolidate their mutual future.” Their artistic alliance became a placeholder for the conjugal bond society denied them. It entwined them for life, as binding as a marriage contract. Even after Preece’s death, Hepworth signed her paintings with her partner’s name.

Why did Preece marry Spencer? Neighbors in the small village of Cookham, they grew close over the years, and it seems likely that once the option presented itself Preece recognized that it could be the answer to her and Hepworth’s straitened circumstances. (Even before their marriage, Spencer had signed over the ownership of his large house to Preece.) She might have also hoped that it would stem some of the gossip about their living arrangements. When the women initially arrived in Cookham, the owner of the first house they’d hoped to buy reneged on the sale at the last minute, supposedly because she’d heard rumors that they were lesbians.

Wilcox cites plenty of evidence from Preece and Hepworth’s private papers testifying to the enduring strength of their attachment (“I want your love so much, there is nothing more,” Preece wrote Hepworth in 1942). Yet when she was talking to anyone other than her beloved, Preece was a master dissembler. In A Private View, Collis summarized her overall impression of her subject: “not a woman of very strong personality. Sensitive and highly strung.” Now that assessment seems entirely misjudged. “Who would have imagined that such a married life could be described outside the pages of fiction?” Collis writes in the postscript to the book, her attention entirely focused on Preece’s story about Spencer’s desires for a ménage à trois between him, her, and Hilda. Yet Collis, it seems, remained oblivious to the triad involving Hepworth, Preece, and Spencer.

In 1978, shortly before her death, Hepworth finally unburdened herself of her secret. She was visiting College Hall—where she’d lodged as a student at the Slade—to bequeath the residence hall her books and prints. Meeting with the principal, Mrs. Witt, she confessed that it was she, not Preece, who’d painted the works sold under her partner’s name. We don’t know why she chose to say so then, nor why to Mrs. Witt, a woman with whom she had no prior relationship.

Only at the end of the exhibition do we glimpse Hepworth as she saw herself. It draws to a close with three self-portraits, the last of which was painted around 1970. A white-haired old woman, clad in a painting smock and with brush in hand, she stares directly ahead. There are no other props to temper the scene, no clue even as to the room in which she sits. Model and artist both, now entirely alone. Shortly thereafter she wrote in her diary about her grief for the woman with whom she’d shared her life: “I try to struggle against my utter loneliness and loss of her.”