Governor Tim Walz, as everybody knows by now, comes from Minnesota by way of Nebraska. He grew up near the eastern Nebraska town of West Point, which is about forty miles from the small city of Norfolk, the childhood home of Johnny Carson, the quintessential late-night talk show host. Carson’s “The Tonight Show” (later “The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson”), which appeared on NBC in the Sixties, Seventies, and Eighties, impressed his Midwestern persona into the nation’s consciousness. Governor Walz, in his first speech as Kamala Harris’s vice-presidential nominee, displayed a sense of comic timing and a flat Nebraska accent remarkably like Carson’s. Those who remember Johnny can replay in their minds his double take, his slow shake of the head at some crazy item in the news, and his pronunciation of the single word, “weird,” which he knew enough not to elaborate on as the laughter built. Walz’s now famous one-word description of Trump & Co. is solidly Nebraskan and from the school of Carson.

Before Walz entered politics, as we also know, he served in the National Guard and taught high school. He earned his B.S. in social sciences education from Chadron State College, in Chadron, Nebraska, in 1989. When news stories about Walz mention this, all the ones I’ve seen add that Chadron is in western Nebraska and leave it at that. More could be said about Chadron. For twenty or so years I passed through it often, as I researched books I was working on, and I consider it sort of a starting-out point for me, as I assume it was for Walz. When I was economizing I sometimes slept in my vehicle on the town streets. If the police rousted me from curbside, I pulled into the local used car lot and parked in the rows of bargains no fancier than my own old Chevy van and blended in, and was left alone. Later I spent weeks, maybe months, in a Chadron motel, near tracks on which freight trains rolled through town. During the days I commuted to the motel-less Pine Ridge Indian Reservation, in South Dakota, or read local newspapers on microfilm in the pleasant and helpful library at Chadron College. Fort Robinson, the army post where the Oglala Sioux chief Crazy Horse was killed in 1877, is about thirty miles west of Chadron. (Now it’s the Fort Robinson History Center.) The death of Crazy Horse was as consequential and ill-omened, in its way, as the political compromise in the same year that gave Rutherford B. Hayes the presidency at the cost of reimposing white supremacy in the South. In other words Chadron, out in western Nebraska, is not nowhere.

Walz met his wife, Gwen, when both were high school teachers in Alliance, which is fifty-five miles to the south. According to National Public Radio, he was teaching a class in social studies and she was teaching one in English in a large shared room with a partition down the middle. On their first date they went to a movie—I guess there was still a movie theater in Alliance then—and afterwards had dinner at Hardee’s, then the only restaurant in town that was not a bar.

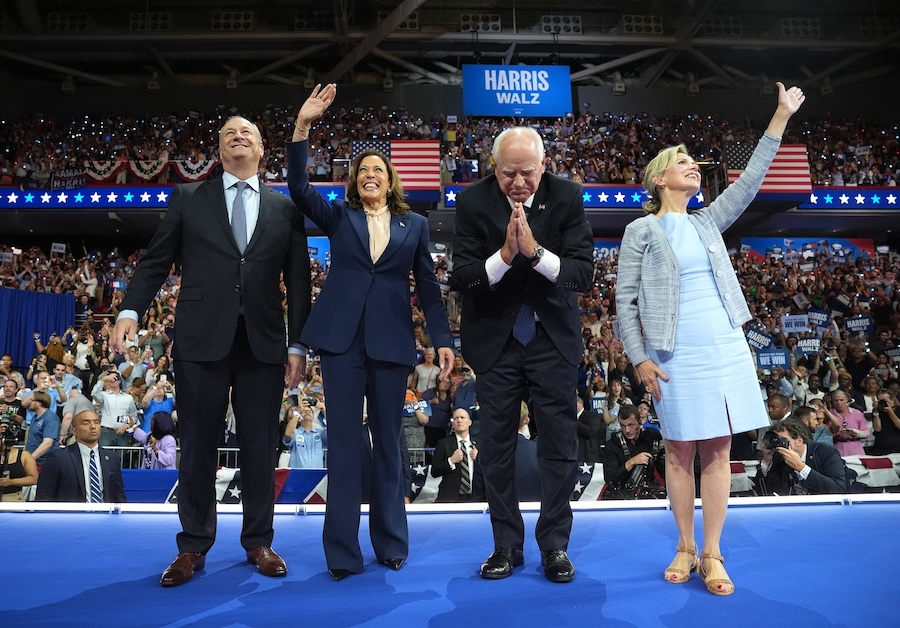

Gwen Walz, née Whipple, grew up in western Minnesota and went to college in Mankato, where she and her husband later taught high school. To my Oglala friends on Pine Ridge, Mankato was a name not spoken but spat, because thirty-eight Sioux were hanged there in 1862 in the largest mass execution in US history. Abraham Lincoln ordered the hangings even as he regretted them. White Minnesotans wanted revenge for the killings of whites in the recent war with the Sioux, and Lincoln needed Minnesota’s support and troops for the Civil War. Gwen Walz works for prisoners and prison reform because, having lived in Mankato, she knew its history. I take this as a sane and encouraging sign. In fact, it’s one of the best things I’ve heard about any spouse on any presidential ticket ever.

Not enough Democrats know enough about the part of the US that’s not the coasts. They may understand this shortcoming, but they never seem to do anything about it. Remember the Clinton Global Initiative? Why didn’t the Clintons retool that into, say, the Clinton Youngstown, Ohio, Initiative, when that city and others like it fell into difficulties? Maybe the party ignores tornados in places like Madison County in Iowa (2022) or Otsego County in Michigan (also in 2022) because they’re among the many rural counties that went for Trump by two to one in 2020. After the train derailment in East Palestine, Ohio, which sickened hundreds with toxic chemicals and shut down the town, why did Trump visit before anybody in the Biden administration showed up? The Dems seem unaware of Midwestern tornados and floods and other in-country disasters and miss opportunity after opportunity to demonstrate they care about the not-coasts. After the September 11 attacks, and after Hurricane Sandy, in 2012, groups and individuals from all over the country sent help to New York City. Why don’t big-money donors in that richest city set up a nonprofit to assist small places after rural disasters? That might improve the reputation of the so-called coastal elites.

Governor and Mrs. Walz lift my spirits because they break the Democrats’ pattern of seeming to prefer the coasts. Trump, for all his etc., does seem to be aware of the overlooked places. Every other time he holds a rally, it’s in a town or small city I’ve never heard of. (Did anyone reading this have any idea where Butler, Pennsylvania, was three weeks ago?) Trump (or his people) may know some of the places, but they fear and falsify the history. They’re good on the geography of the US, but on dark areas like slavery or the treatment of Native Americans, they don’t want to know and don’t want children to know. The Walzes seem to know and care about the places as well as the history. And candidate Walz should use his Carson-like gifts whenever possible. Before red and blue was a thing, the whole country loved Johnny.