New York City’s greatest natural resource—its cast of characters—inevitably attracts prospectors, but attempting an industrial-scale mining operation can be unwise. Efforts like the Facebook-page-turned-coffee-table-book Humans of New York or the Instagram empire of “New York Nico,” the city’s “unofficial talent scout,” illustrate how easily documentarians trying to represent such a vast and various range of people can end up repeating themselves, relying on memeified stock figures, or hanging around Washington Square Park when business is slow.

How To with John Wilson, which recently aired its third and final season on HBO, has captured New York’s tapestry of oddballs nearly as well as I can imagine by taking a more nonchalant approach, letting the city’s street theater unfold in the background as John Wilson pursues his various preoccupations. Each episode intersperses extensive B-roll of unusual things Wilson sees on the street with extended interviews of (mostly) New Yorkers and is loosely structured around interpersonal dilemmas or urban issues—“How to Make Small Talk,” “How to Throw Out Your Batteries,” “How to Find a Spot.”

How To takes in an enormous catalog of images but makes no claim to comprehensiveness, remaining anchored by the perspective of a gentle, cinephilic, socially anxious Ridgewood dirtbag. In one episode, “How to Remember Your Dreams,” Wilson recalls how his childhood friends excluded him from their Dungeons and Dragons game. “I completely rejected fantasy from there on out,” he says in his signature monotone—over a shot of a plastic castle in a trash can. “I started to only read books about real stuff” (man in a cowboy hat on a park bench reading from the New York Evidence Handbook), “and became obsessed with the authenticity of documentary filmmaking” (a camera crew filming inches from the face of a violinist playing emotively, crouched down in tight pants on a pier).

Some episodes have genuinely investigative segments—you’ll come away from the first season better understanding how scaffolding works—but all are highly digressive. Nonetheless, they are carefully structured to understated comedic effect. (In addition to Wilson and Michael Koman, who wrote almost every episode together, notable contributing writers include Alice Gregory and Susan Orlean.) “How to Appreciate Wine” begins with Wilson confessing his insecurities about selecting wine for a party and receiving some incomprehensibly technical guidance from a wine salesman. This is juxtaposed with footage of a collector of historical military rations sampling his own fare: “It has sort of a…mustiness,” he says thoughtfully. “Sort of a paper-type taste to it.” At a wine-tasting cruise full of officious connoisseurs, Wilson reflects on the desire to fit in, which leads to memories (and old footage) of the time that his a cappella group at SUNY Binghamton unwittingly performed in a summit hosted by the sex cult NXVIM, which was apparently trying to groom undergrads. He decides to be truer to himself and embrace energy drinks, which he actually likes, but an elaborate series of events leads him to stumble unannounced into an undeniably cult-like baby shower at the Florida mansion of the CEO of the beverage company Bang Energy.

How To started as a solo project: a series of shorts that Wilson made and posted to Vimeo in his time off from shooting infomercials and other freelance work. It ultimately caught the attention of the comedian and director Nathan Fielder, who helped sell it to HBO executives, but the show still feels pleasantly shaggy and anti-commercial. In one episode, Wilson struggles to describe How To to an unblinking mortgage broker, whom he is trying to convince of his financial solvency. “It’s kind of like memoir, essay,” he says. “It takes place in New York.” Her face hardens on learning his only asset is one share of stock in Domino’s Pizza. “We don’t want to lend to somebody who miraculously got a huge project and it will never happen again,” she says.

How To is indeed about New York, though Wilson will leave town to follow his topic wherever it leads him, and it is about John Wilson, though he is hesitant to reveal much. But its true organizing principle is the search for “rare images,” as he puts it. He has an obsessive collector’s spirit, and the show draws on over a decade of filming and sifting for gems. (In the show’s HBO incarnation, Wilson is assisted by a team of shooters, but has said that he still personally films about three quarters of the images.) The footage might be of a skunk wandering through the lobby of a credit union, or an elderly personal trainer admitting that he felt “proud” when he learned that several of his clients had been involved in the plane hijackings on September 11: “We may not agree with them, but they were committed.” When something truly remarkable happens, Wilson will usually just respond with a nasally “Wow.”

For my money the show’s most surprising set-piece is an “all-referee dinner”—a party for a soccer referees’ association in Long Island. It’s not so improbable in hindsight, but I had never considered that such a situation might exist. Wilson attends the event hoping to learn about fairness (the episode is titled “How to Split the Check”), but it swiftly devolves into chaos and recrimination, edited with brilliant comedic timing. The league officials loudly chide the refs about listening and cleaning up as if they were children, while the refs, for their part, are full of pent-up resentment. “They don’t pay me,” says one guy, pointing at the head ref sitting directly across from him, who brays nervously with an open mouth full of ziti. People start loading cans of Sprite into their bags and taking extra food. “You have to get your money’s worth,” one man says darkly. Like many moments in the show, it leaves a viewer wondering what might be on the other side of the millions of closed doors in New York—how many self-enclosed communities there are with their own rules, jealousies, alliances, thefts of one another’s whistles.

Wilson is interested in systems—not in institutions, exactly, in the mode of Frederick Wiseman, but in chains of production. Any oddity, he seems to have realized, is likely to have an even odder constellation of people behind it. If there’s a scented bowling ball, then there’s someone who has devoted a significant part of his life to imbuing a bowling ball with coffee-cake odor, and you can probably tour his factory. See a “Quick Evic” billboard near elevated subway tracks, and you can meet the man behind that business, as well as his own hostile landlord. Following these chains often leads Wilson to unusual industry gatherings. He is our great poet of the convention: a scaffolding expo, cryonics conference, vacuum cleaner collectors’ meet-up, convention for convention planners.

These surreal, fluorescent halls suit Wilson’s visual style—he tends to film people awkwardly stranded in the middle of wide static shots. Perhaps his interest in capitalism’s effluvia comes from the years he spent working on infomercials, during which, as he says at one point in the show, he helped “create some of the most grotesque content on the planet.” He has a nonjudgmental appreciation for niche interests that bring people together, especially men who might struggle to connect in other ways. Among the most extended and touching segments are the one about the vacuum collectors—many of whom, Wilson implies, are closeted gay men living in and around Scranton, Pennsylvania—and one about a meet-up of depressive superfans of the movie Avatar.

The show’s most openly memoiristic theme is Wilson’s fear of commitment, which he mentions repeatedly yet glancingly enough that it would be easy to mistake him for any old emotionally unavailable film-loving guy. Occasionally, however, he reveals an obsessive streak—he made a movie a day while growing up, he documented everything he did each day in bullet points for a decade—that reminds the viewer of the enormity of his project and the extent to which it must have required, or enabled, him to step away from the social world. “You’re always used to having some kind of protective mechanism,” says an interior designer whom Wilson has asked for advice about a plastic-covered armchair. “In some ways [your camera] has connected you more than ever with people, and yet there’s always a bit of a separation.”

At one point Wilson reads through his diaries and is horrified to find that they consist of endless recitations of what time he woke up, what he ate for lunch, and what movies he watched, occasionally punctuated with emotionless recordings of breakups. “Sam over. Scrabble. Told her no relationship.” This diary calls to mind another in one of his Web shorts, in which he meets with the director Caveh Zahedi (though he doesn’t name him) and films him reading from a journal of regrets accrued during the past twenty years. The selection he reads doesn’t sound all that different from John’s: “I regret shaving off a few extra facial hairs without bothering to put on more shaving cream.”

Zahedi has his own documentary series about life as an independent filmmaker in New York City: The Show About the Show, which is in some ways brilliant but has caused extreme distress to numerous people close to him, simply replacing them with actors to keep reenacting their encounters long after they beg or demand to be left alone. Like How To, Zahedi’s show is a self-portrait of a compulsive hoarder of memory and reality. But The Show About the Show is a kind of mirror reflection of Wilson’s project: where How To sprawls outward, blurring the boundary between the world and Wilson, Zahedi’s show spirals inward as it progresses and Zahedi alienates more and more friends, colleagues, and loved ones.

Often Wilson’s approach creates a sense of wonder and openness: the title promises viewers that this will be a show about letting the world and all its mysterious spokespeople guide them. Wilson often films his initial interactions with his interviewees, many of whom gladly welcome him into their homes. The masterful finale of the first season, for instance, is initially about Wilson’s attempts to cook a risotto for his elderly landlady before turning into a document of the first days of Covid. At one point, upon seeing an Italian flag on someone’s garage in his neighborhood, Wilson wanders through their open front gate. Before long the man who lives there is not only giving him an energetic tutorial on how to cook risotto but showing off his paintings of the southwest. “I believe there was also, you know, alien beings over there, that gave us a little bit more knowledge.”

There is, of course, a camera involved, and Wilson often gets access to places by dropping the name “HBO.” But many people just seem eager to share their stories. Given that he’s not a warm or probing interviewer (“Are you an organ donor, at all?” is a question he uses twice in one episode to try to spark conversation), he does best with subjects who have a spiel ready. Sticking with people who are big talkers or have something to sell mostly allows Wilson to skirt the central ethical dilemmas of documentary: whether it exploits its subjects or demands a false authenticity. You get the sense that the foreskin regeneration activist comfortably stretched out in bed without pants, explaining the benefits of a horrifying stretching device of his own invention, might be doing and saying the same thing to someone else if Wilson wasn’t there filming.

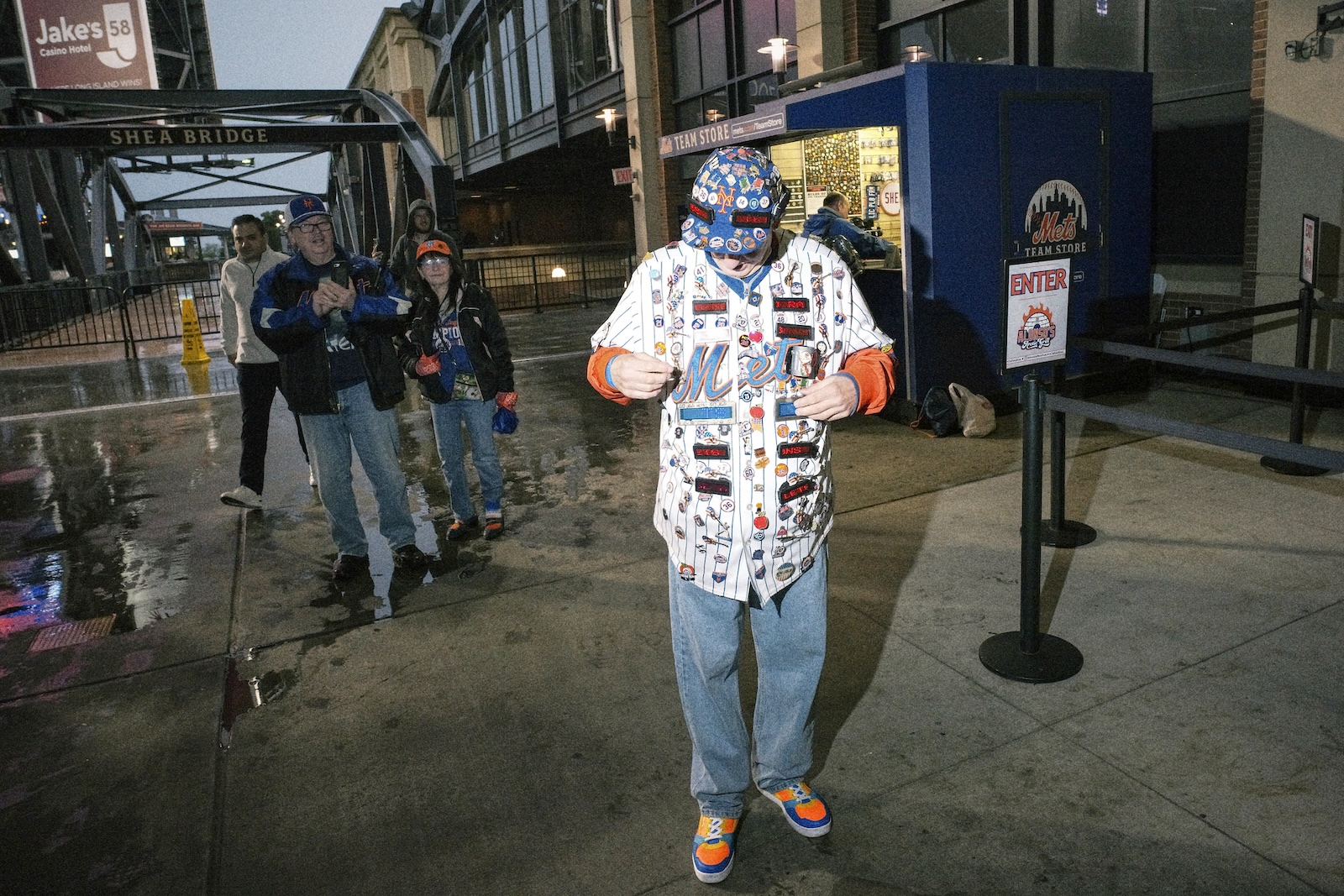

Once his subjects get going, Wilson often manages to gently nudge them away from their default settings, generally just by spending more time with them. In one episode he goes to a rained-out baseball game, where he meets an older man decked out from head to toe in flashing battery-powered Mets paraphernalia. Following him home reveals a quiet domestic scene—he is the caretaker of his elderly father, who looks almost identical to his son, minus the getup. “I tell everybody, you should have seen me when I was alive,” the father says ruefully.

By the third season, Wilson seems a little tired of having to search for fresh material. Part of the delight of seeing Wilson pursue his nearly random whims is that it creates the feeling that there are extremely idiosyncratic and wonderful happenings everywhere, waiting to be discovered. When he seeks out self-consciously wacky events—“thankfully, you were at a cat show recently”—it punctures that illusion. He goes on a trip to Burning Man but is ultimately prohibited from using the footage, a development he tries to spin into something meaningful about the restrictions of private space, but it just feels like a dead end.

In another episode he travels to a West Virginia community of electrosensitive people, who have moved to a remote area in order to escape Wi-Fi and other electromagnetic waves that they believe to be harmful. There are some good moments, but nothing comes close to the insanity in the first part of the episode, which is about noise pollution in New York. (It features, for example, a hipster couple who incurred a noise complaint for playing high-pitched metallic techno at 1 AM to celebrate their baby’s birthday. “When they asked me to end at midnight, I was honestly pretty surprised that, you know, someone close to our age would be going to bed then,” says the father while bouncing his baby, who is named Skylo. “I never have gone to bed at that hour.”) Besides, the number of VICE articles about electrosensitive people makes you think they are better left alone.

The season also includes metacommentary about the show’s reception. Wilson is simultaneously creeped out by the glamorous circles he now finds himself on the outskirts of, unsatisfied by mainstream success, and irked about having to go on talk shows and answer questions about whether his footage is real. In “How to Watch Birds,” he discovers a conspiracy theory about the Titanic and interviews a man named Bruce who has written a book on the topic. They end up hanging out for several days near Bruce’s home in Tennessee, visiting kitschy museums and a monkey emporium. Bruce gradually comes into focus as a self-important but vulnerable character, a down-on-his-luck ex–police sergeant trying to maintain his self-image through Titanic expertise. “[When] a little kid gets killed, gets murdered, that’s not good,” he says, reflecting on his police days in a diner, between loud spoonfuls of chicken soup. “To see the faces of the dead, the dead faces, they’ll never leave me.” He soon flips the interview on Wilson. “Who’s your favorite Beatle?”

As the two grow more intimate, Wilson asks Bruce the animating question of the episode: Was it unethical to fake a shot earlier in the show of a toilet exploding with sewage—an event of which he had seen a video, but recreated on a soundstage? With deadly seriousness, Bruce confides in Wilson that he would sometimes fabricate evidence as a police officer: “Sometimes you’ve gotta fake some things, because if you don’t, it could turn into a worse situation than what you have.”

It’s a shocking moment, but Wilson swiftly undercuts the tension with a clunkily fabricated subplot about an exploding car, meant to cast doubt on whether events in the show more broadly have been manipulated or are fictional. The device smacks of the influence of Nathan Fielder, whose interest in simulation—and in gleefully blowing an HBO budget—was on display in The Rehearsal. It feels out of place in How To, which is guided by the joy of seeing something truly unexpected. If it’s fake, what’s the point?

Surely there have been some fabrications, especially when it comes to the order of events. Did Wilson really start reflecting on energy drinks because he saw an employee at the scented bowling-ball factory drinking one? But the exploding car is so obviously fake that it casts no meaningful light on how the show might actually be put together. Wilson’s Web short “How To Act on Reality TV,” which follows a charismatic but uncredentialed man who coaches a handful of lost souls on how to become reality stars, offers far more interesting insights into the sometimes adversarial, sometimes mutually beneficial relationship between producers and participants, not just on reality TV but in documentary in general. At a whiteboard, the instructor, Robert Galinsky, does some quick profiling of his students—“counterculture kid,” “communist Latina”—telling them that this is how they will be perceived by producers, and they should play into their types. “You guys have to give them that rich material so they can write the story.” Wilson ends the film with a painfully long shot of one of the students, a man named Shannon, after their interview ostensibly ends—more than a minute of silence. Shannon at first seems uncomfortable and looks off to the side, but then completely shuts off any expression, gazing blankly into the camera, before finally getting up and walking away.

In a conversation with Zahedi from 2020, Wilson says that he began the project that became How To in his twenties in part because he was feeling insecure that his friends had more exciting lives:

I was a really bad storyteller and I didn’t have any good stories, so the movies, for me, were a way to start just trying as much stuff as I possibly could, and maybe turn it into something. And just start to have stories and make interesting work and have something to talk about.

This is a tactic familiar to many naturally shy people: become observant when you feel you don’t have much to offer, and craft those observations into a self. But it’s not quite the same as actually sharing yourself. Critics have praised the final season of How To for being more personal than the earlier two, but Wilson seemed to me to make more significant missteps as he took more control over shaping the material. When you reflect on yourself through what you see in the world, other people’s stories come to appear meaningful only insofar as they fit into your own. In “How to Work Out,” Wilson stumbles upon a pumpkin-growing festival near Poughkeepsie that he feels neatly ties in with the episode’s themes about masculinity, competition, and “getting big”—by which he means both physically big and famous. “Just when you thought you had run out of things to impress the television academy with, these people had just given you the perfect metaphor. And not a single person there had any idea,” says Wilson in voiceover over a shot of a slack-jawed teen.

This method is innocuous when the metaphor is an easygoing pumpkin festival (Wilson also displays a genuine appreciation for the participants’ dedication to growing for growing’s sake). But elsewhere in the season it has more troubling implications. The final episode, “How to Track Your Package,” is characteristically digressive, but it ends up in an organ-themed pizza restaurant in Scottsdale, Arizona, where a man on a rotating dais plays a massive instrument that drowns out all conversation. Here Wilson meets an elderly man named Mike who is a prominent member of a cryogenics organization. After Wilson asks Mike whether having children—instead of being dipped in liquid nitrogen—might be a way to preserve oneself, Mike gradually reveals that as a young man he had secretly castrated himself because “I had a lot of sexuality that I didn’t want,” going into detail about the method and effects of the operation. It’s obviously an extremely vulnerable thing to share, especially because Mike is stooped almost double with age, dwarfed by his giant suede armchair. It’s possible that he genuinely wanted to reveal this information, and fully understood the scope of the project, but Wilson follows the interview with a tasteless pun. In a closing monologue he says, “Maybe it’s okay if your package takes a while to get where it’s going, because it’s better than not having any package at all.”

There’s a moral criticism to be made here, but also an aesthetic one—this man’s story is more interesting and complex in the full setting of his life than wrapped up into a symbol. (There is a poignant connection between cryonics and the episode’s themes of preservation and letting go, but it’s one that has already been made abundantly clear by a characteristically well-crafted segment at an unholy convention for Mike’s organization, Alcor.) In TV Guide, an interviewer asked Wilson about ending the show with that interview. He answers that it hearkens back to the first shot of the season, of the Empire State Building positioned between a man’s legs to look like a giant erection, and says, “So much of the show deals with the denial of pleasure, and having to find circuitous ways to deal with not being able to satisfy yourself in the city.” It’s not clear what denial of pleasure he has in mind (not being able to find a parking spot?), but in any case it seems far from whatever Mike was experiencing in 1969. Positioned as it is as the crux of the series, this painful testimony risks coming across as merely the rarest image of all.